About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own. This is my less-technical blog on non-work topics. For my main blog, visit https://brooker.co.za/blog/.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

Building My Own Watch: The Intro

I like making things. Sometimes furniture, sometimes machines, sometimes RC cars. Whatever takes my fancy at a given moment. What I don’t like is making tiny fiddly things with extremely tight tolerances.

So I decided to make a watch.

More than a decade ago, I inherited a watch that my grandfather was given when he completed 20 years at Unilever. It’s not worth a lot of dollars, but it worth a ton of memories. At some point it’d been dropped, the crystal was cracked, and the mechanism wasn’t working. I considered sending it away to fix it, but instead decided to get good enough at working at watches that I could fix it myself. That started a bit of a journey.

That journey got me here, wanting to make my own watch.

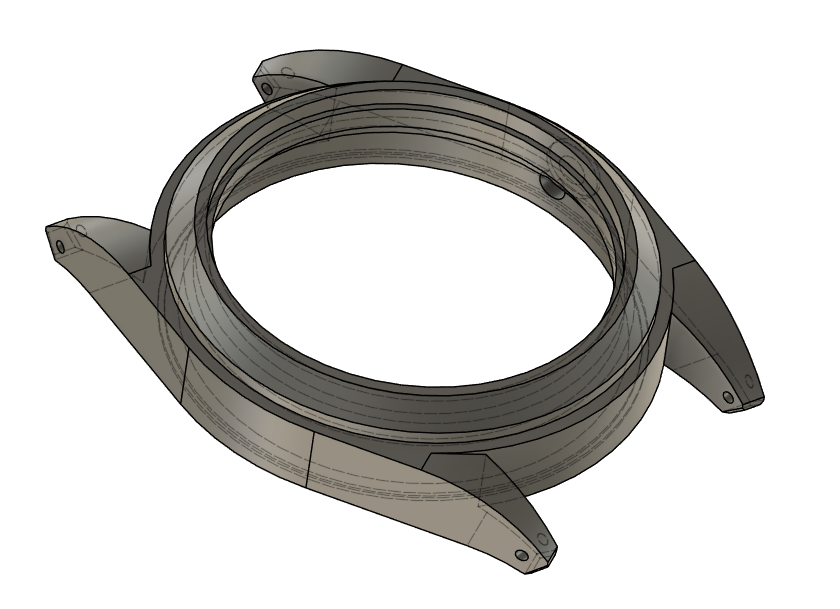

Eventually, that might mean making my own movement (the thing in the watch that actually does watch stuff). But, to start, I decided to make just the outside parts: the case, crown, hands, dial, and strap. The bits the movement goes in.

The first custom watch I built was assembled from eBay parts: case, movement, crystal, crown, stem, strap, dial, and hands.

It came out pretty well! Not perfect, but along the lines of what I wanted.

Choices: The Guts

The first choice is what style of watch to build. There are divers and chronographs, field watches and pilot’s watches, tool watches and dress watches, wrist watches and pocket watches, even the Ankh-Morpork night watch. I tend to like the simplistic end of the scale: the field watch with it’s basic readable face, three hands, and few features.

Second is the type of movement. Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of modern watch movements: mechanical ones with gears and wheels and springs, and quartz ones with a tiny crystal and an even tinier computer3. Quartz movements are better in every quantitative measure: they’re lighter, they’re cheaper, they’re more robust, they keep better time, they don’t need constant winding or wearing. Some can even listen to WWVB. Mechanical watches, on the other hand1, are more fun. They have cool moving bits you can watch. A little bit of special magic. They have link to the past work of folks like John Harrison (no, not that other John Harrison).

The mechanical movement I chose is Seiko’s NH35. It’s relatively cheap (incredibly cheap for what it is), widely available, robust, and solid quality. The NH35 is a kind of mechanical movement called an automatic, because it winds itself up over time as its worn, by stealing picojoules of the wearer’s precious life force throughout the day.

The Seiko NH series is pretty accurate, only around 200,000,000,000 times worse than an atomic reference.

Choices: Materials

The next question is what to make the watch out of.

If you live in a city, you can go out today and buy a watch with a case made of stainless steel, gold, wood, plastic, brass, silver, ceramic, platinum, titanium, glass, and probably a handful of other things. It’s a small box, without a ton of constraints.

Glass is a pain to work, as are ceramic and titanium, so those are out. Gold, silver, and platinum seemed a little rich for a first attempt. Stainless steel is cool, but boring. As is aluminium. Plastic and wood seemed a bit goofy. So I picked brass.

Or, rather, bronze. 954 Aluminium Bronze to be exact. Aluminium bronzes are cool: they look nice, are easy to work, don’t contain any lead2, and resist corrosion by covering themselves in a nano layer of strong aluminium oxide. Brass’s density makes for a nice weight (I find aluminium and titanium cases to be weirdly light). But, mostly, it’s easy to machine. I’ll likely make a stainless version later.

The second choice is the crystal, that little glass window at the front. It may surprise you to learn that a lot of high end watches have a plastic crystal. Acrylic is tough, clear, easy to buff to a high shine, and cheap to make into all kinds of shapes. Objectively, like quartz, it may be the best choice. The most boring choice is plain old glass. Like the stuff you’d pull a pint into. Glass is kind of in the middle. At the other end from plastic is sapphire. Yes, sapphire. Turns out you can grow really big sapphires for cheap and make watch crystals out of them and you have a crystal that’s extremely hard. Only a handful of things like diamonds and SiC are harder than sapphires.

The downside to sapphire is that its brittle. And my plan is to interference fit the crystal. As in make a hole slightly smaller than this thin slice of crystal, and press fit it into place, stretching the metal to keep it in. Fun!

The dial I have in mind is going to be titanium, with some custom CNC ‘guilloche’. More on that in a future post.

Choices: The Looks

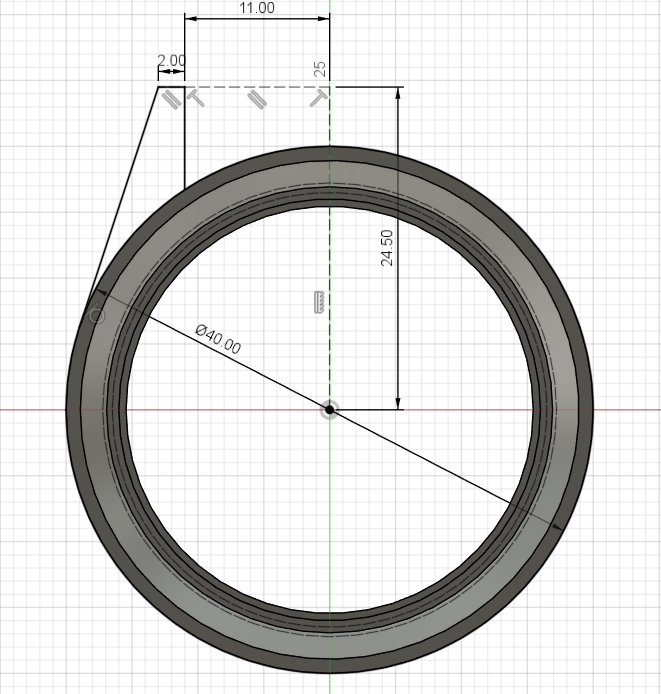

I wanted to design something that was my own, but also with a classic look. The closest existing watch to the profile I wanted is probably the Tissot Gentleman. But I wanted chunkier, and less dressy. Something classic.

The dial portion is quite complex: a bore for the crystal, a bore for the dial to sit on, a bore to hole the movement in place, and a bore that the back threads onto. By comparison, the case profile is very simple: 22mm strap size, 2mm wide lugs, and a simple tangent picking up the round from the lug.

I like tangents.

Most of the external parts of this design are entirely aesthetic, but the internals need to be held to a fairly high precision. Mating surfaces for the crystal, the crown gasket, and the back gasket need to be especially tightly toleranced to keep water and dust out.

The story continues in the second part.

Footnotes

- The left hand, most likely.

- My entire workshop is lead-free, or as close as I can get it. Leaded metals, from brass to free-machining steels, are a joy to work with, but environmental lead is something I just don’t want around my household.

- The exception is the weird and wonderful Seiko Spring Drive, which is a mechanical movement governed by a quartz oscillator and tiny microcontroller. It’s not quite a quartz watch, and not quite a mechanical watch.