About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

Decomposing Aurora DSQL

Earlier today, Alex Miller wrote an excellent blog post titled Decomposing Transaction Systems. It’s one of the best things I’ve read about transactions this year, maybe the best. You should read it now.

In the post, Alex breaks transactions down like this:

Every transactional system does four things:

- It executes transactions.

- It orders transactions.

- It validates transactions.

- It persists transactions.

then describes how these steps map to traditional OCC and PCC systems, research designs like Calvin, and real-world systems like FoundationDB.

How do these steps map to Aurora DSQL?

An overview of DSQL’s architecture may be useful if you haven’t been following along so far:

Now, an hour of video and 20 minutes of reading another post later, we’re back. Let’s dive in.

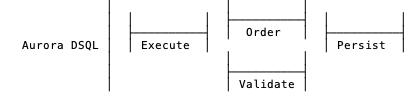

Executing a transaction means evaluating the body of the transaction to produce the intended reads and writes.

Aurora DSQL executes transactions on a horizontally scalable fleet of Firecracker-isolated, PostgreSQL-powered, query processors. At this stage there’s no coordination at all. MVCC is used for reads during execution, and no writes escape the query processor running that particular transaction. See this post for more on this step.

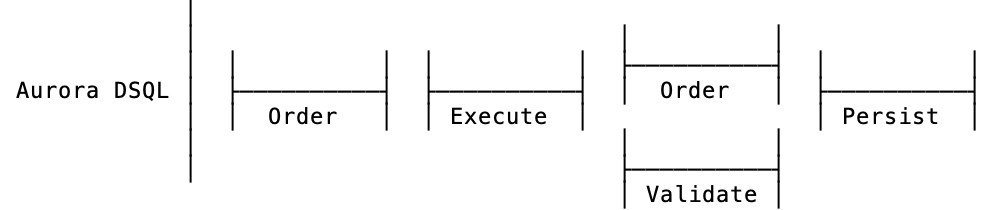

Ordering a transaction means assigning the transaction some notion of a time at which it occurred. Validating a transaction means enforcing concurrency control, or more rarely, domain-specific semantics.

In DSQL, ordering and validating happen in parallel, done by the adjudicators involved in the transaction. Each adjudicator provides a range of possible orderings (not after, not before), and one final adjudicator makes the final ordering decision. Similarly, each involved adjudicator weighs in on validation, with one final adjudicator checking that everybody says yes. Strictly, the final-final order is chosen only after validation completes, but the ordering and validation protocols run in parallel. See this post for more.

Persisting a transaction makes making it durable, generally to disk.

The transaction is persisted by writing it to a replication log (the Journal). At this point it is durable to stable storage in multiple availability zones (or multiple regions).

DSQL then goes through another step, which is applying that persisted change to the storage nodes to make it available to reads. This happens after the transaction is committed, and isn’t actually required for durability, just visibility. The MVCC scheme ensures that clients don’t see this gap between committed and visible. This slightly breaks Miller’s model, but it can be rolled into persisting without too much stretching of the truth.

A Couple More Details

MVCC databases may assign two versions: an initial read version, and a final commit version. In this case, we’re mainly focused on the specific point at which the commit version is chosen — the time at which the database claims all reads and writes occurred atomically.

DSQL’s MVCC scheme does exactly this, establishing two orderings. One is a read-time ordering, where a read timestamp $\tau_{start}$ is picked, and all reads are performed on a consistent snapshot at that timestamp. Then, at commit time, a commit timestamp $\tau_{commit}$ is picked, and the writes occur atomically at that time. A serializable database must maintain the illusion that $\tau_{start} = \tau_{commit}$, but at DSQL’s default snapshot isolation level it is sufficient to ensure that $\tau_{start} \leq \tau_{commit}$, and that no write-write conflicts have occurred between the two times.

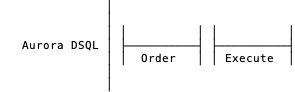

Finally, and again because of the MVCC scheme and use of physical clocks, DSQL doesn’t require a validate step on read-only transactions, or the second ordering step. Like most databases, it also doesn’t require a persist step following a read-only commit. Transactions that only do reads have an even simpler breakdown.

Coordination

Another useful way to use Alex Miller’s model is thinking about which steps require coordination, either fundamentally or in any given implementation.

Fundamentally, execution doesn’t (or, at least, coordination can be replaced with synchrony during execution using MVCC and physical time). Ordering doesn’t strictly (physical time again, though you have to be super careful here). Validation does seem to require coordination. Persistence requires replication (at least in distributed databases), but that doesn’t imply it requires coordination. So, if coordination is what you’re optimizing for (such as because you’re running across multiple regions, or care deeply about scalability), then optimization for the validation phase makes sense.

This mirrors the choice we made with DSQL, and reflects the core reasoning behind our choice of MVCC and OCC. In DSQL’s design, execution requires no coordination, persistence requires no cross-shard or cross-replica coordination, and validation and ordering require only coordination between the minimal number of shards.