About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

DSQL Vignette: Transactions and Durability

In today’s post, I’m going to look at the other half of what’s under the covers of Aurora DSQL, our new scalable, active-active, SQL database. If you’d like to learn more about the product first, check out the official documentation, which is always a great place to go for the latest information on Aurora DSQL, and how to fit it into your architecture. Today, we’re going to focus on writes (INSERTS, UPDATES, etc), and how transaction isolation works in Aurora DSQL.

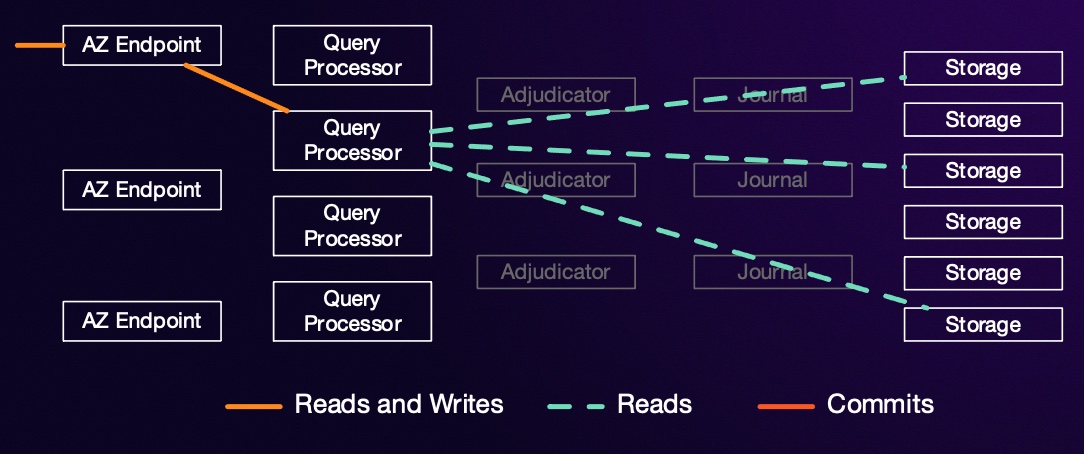

As I wrote about yesterday, reads in Aurora DSQL are done using a multiversion concurrency control (MVCC), allowing them to scale out across many replicas of many storage shards, and across a scalable SQL layer, with no contention or coordination between readers. We’d love to be able to achieve the same properties for writes, but the need to ensure that transactions are isolated from each other (the I in ACID), and ordered relative to each other (needed to get strong consistency) requires that we do some amount of coordination.

The story of writes in Aurora DSQL is how and when that coordination happens.

Let’s consider an example transaction:

START TRANSACTION;

SELECT name, id FROM dogs ORDER BY goodness DESC LIMIT 1;

UPDATE dogs SET latest_treat = now(), treats = treats + 1 WHERE id = 5;

COMMIT;

We do the read part just like we did the read part of yesterday’s transaction: we choose a start time ($\tau_{start}$), and perform all our reads at that start time against our MVCC storage system. The writes proceed in a similar way: executing the UPDATE simply writes down a planned change locally inside the Query Processor (QP) that’s running this transaction. No replication, durability, or writes to storage have occurred yet. That’s important, because it means that the UPDATE (like the SELECT) is fast, in-region, and often in-AZ.

Writing Takes Commitment

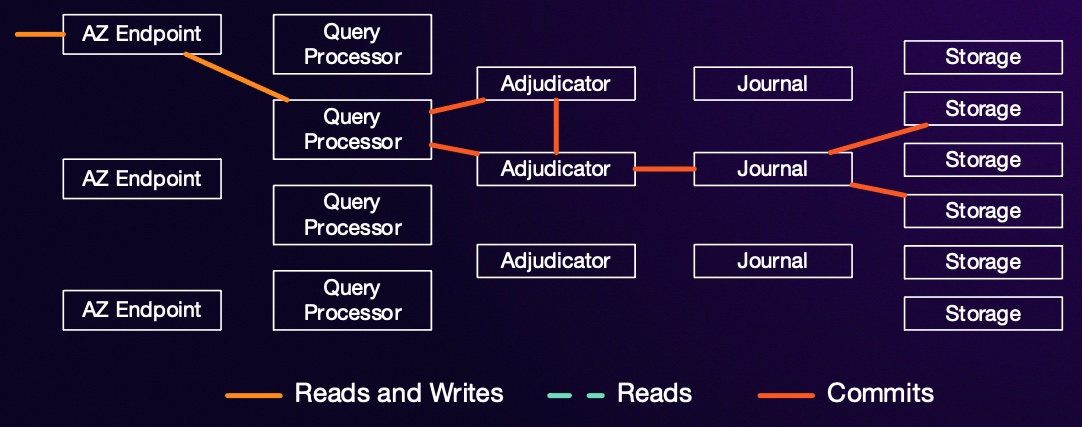

The really interesting thing start with the COMMIT. We need to do three things to commit this transaction:

- Check whether our isolation rules will allow it to be committed (or, alternatively, it attempts to conflict with other concurrent transactions and must be aborted).

- Make the results of the transaction durable (the D in ACID) atomically (the A in ACID).

- Replicate the transaction to all AZs and regions where it needs to be visible to future transactions.

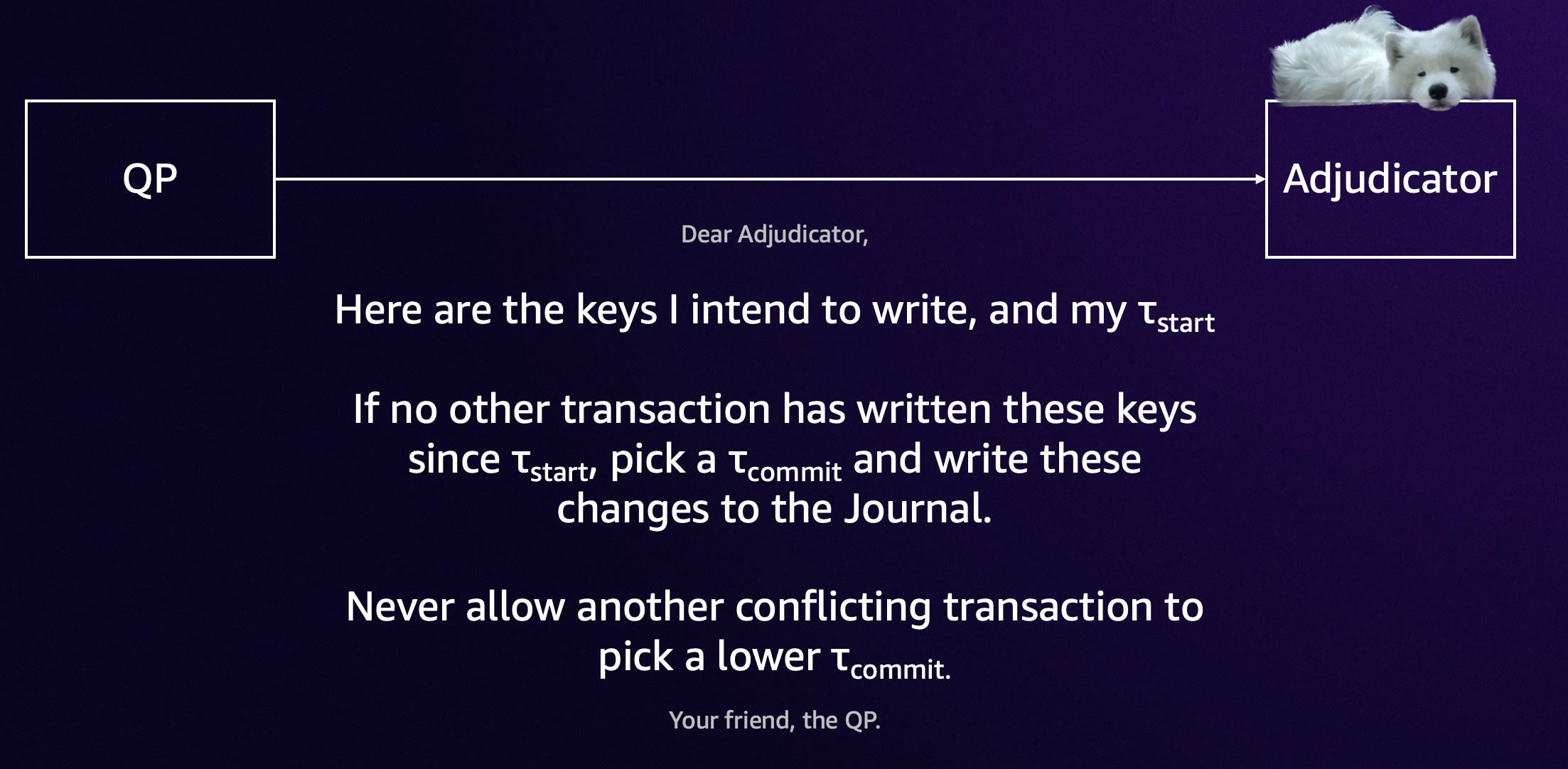

First, we pick a commit time for our transaction (we’ll call it $\tau_{commit}$). To achieve our desired isolation level (snapshot isolation1), we need to know if, for every key this transaction wants to write, any other transaction wrote the same key between $\tau_{start}$ and $\tau_{commit}$2. We don’t need to worry about transactions that committed before $\tau_{start}$, because we’ve seen all their effects. We don’t need to worry about transactions that commit after $\tau_{commit}$, because we don’t see any of their effects (although they may end up not being able to commit because of the changes we made).

In DSQL, this task of looking for conflicts is also disaggregated. It’s implemented in a service we call the adjudicator. Like all parts of DSQL, the adjudicator is a scale-out component that can scale horizontally, but by breaking this out into a separate service we can optimize that service for checking conflicts with minimal latency and maximum throughput. If a transaction writes rows that span multiple adjudicators, we run a cross-adjudicator coordination protocol, which I won’t talk about in detail here.

Once the adjudicator has decided we can commit our transaction, we write it to the Journal for replication. Journal is an internal component we’ve been building at AWS for nearly a decade, optimized for ordered data replication across hosts, AZs, and regions. At this point, our transaction is durable and atomically committed, and we can tell the client the good news about their COMMIT. In parallel with sending that good news, we can start applying the results of the transaction to all the relevant storage replicas (making new versions of rows as they come in).

Optimism

You might recognize this as a description of Optimistic Concurrency Control (OCC)3. That would be astute, because OCC is exactly what’s happening here. In particular, we’re combining multiversion concurrency control (MVCC) to allow strongly isolated reads without blocking other readers or writers, with optimistic concurrency control (OCC) which allows us to move all coordination to COMMIT time. That’s a big win, because it means we only need to coordinate (between machines, AZs, or regions) once per transaction rather than once per statement. In fact, I believe that Aurora DSQL does the provably minimal amount of coordination needed to achieve strong consistency and snapshot isolation, which reduces latency.

That’s not the only reason we chose OCC. We’ve learned from building and operating large-scale systems for nearly two decades that coordination and locking get in the way of scalability, latency, and reliability for systems of all sizes. In fact, avoiding unnecessary coordination is the fundamental enabler for scaling in distributed systems. No locks also means that clients can’t hold locks when they shouldn’t (e.g. take a lock then do a GC, or take a lock then go out to lunch).

OCC does have some side-effects for the developer, mostly because you’ll need to retry COMMITs that abort due to detected conflicts. In a well-designed schema without hot write keys or ranges, these conflicts should be rare. Having many of them is a good sign that your application’s schema or access patterns are getting in the way of it’s own scalability.

At Aurora DSQL’s snapshot isolation level, OCC aborts will only occur when two or more concurrent transactions attempt to write the same keys4. The best way to avoid aborts is to design your schema in a way that avoids write hot spots, and to pick write keys with uniformly (or nearly uniformly) distributed heat. As a rule of thumb, you want the heat on your hottest write key to remain constant as the overall load on your database rises.

What Goes on the Journal

A couple paragraphs up, I mention that once the adjudicator is happy with a transaction, it gets written on the Journal. At this point, the transaction is committed: it’s durable, it’s put in order, all consistency and isolation checks have passed, and it can no longer be rejected. Storage replicas which are interested in the keys in the transaction now must apply it to their view of the world, and make it visible to readers at the right time. What goes on the Journal isn’t requests for transactions, but committed transactions.

This means that storage replicas don’t need to coordinate at all when they consume the journal. There’s no atomic commitment protocol like 2PC. There’s no consensus protocol like Raft or Paxos. They just consume the journal, and apply its changes locally.

If you’re familiar with the database literature, you might notice some parallels between DSQL’s approach and deterministic database systems (like Calvin). In some sense, DSQL’s QP converts an interactive SQL transaction with all its nondeterminism into a deterministic transaction to be submitted to the deterministic write and storage path. The analogy here isn’t exact, but the parallels are interesting. We’ll write about them more when we write up Aurora DSQL’s design more formally.

Consistency

In my post about reads, I mentioned how readers pick a $\tau_{start}$ then ask the storage system to do all their reads as of that time. I left out a crucial part of the picture: the storage system can only do this once it knows that it’s seen all transactions with $\tau_{commit} \leq \tau_{start}$. If new transactions come along, then the reads are invalid and we’ve violated our consistency promise. So how does storage know?

The way it knows is because of part of the adjudicator’s contract: when the adjudicator allows a transaction to commit at $\tau_{commit}$ it also promises to never commit another transaction at an earlier timestamp. Once storage has seen a transaction with a timestamp greater than $\tau_{start}$ from every adjudicator, it knows it has the full set of data. But that could take a long time, especially if there write rate is low. We solve this with a type of heartbeat protocol, where adjudicators promise to move their commit points forward in lock step with the physical clock, and share that commitment with storage. Making that efficient and fast was a major design challenge, and I’m not going into the details here.

Not Just Scale

I’ve written a lot about scalability so far, but DSQL’s disaggregated architecture is about a lot more than scalability. We get significant durability, fault tolerance, availability, and performance consistency benefits from this approach. There’s no single machine, link, or even datacenter that make reads or writes stop for a DSQL cluster, and no single place where data is stored.

Availability is the most important property we get from disaggregation and distribution. Aurora DSQL is designed to remain available, strongly consistent, strongly isolated, and durable even when an AZ becomes unavailable (for single-region clusters), or when a region becomes unavailable (for multi-region clusters). Tomorrow’s post will go into how that works.

Footnotes

- Equivalent to PostgreSQL’s

REPEATABLE READisolation level. - We call these conflicts write-write conflicts. If Aurora DSQL implemented

SERIALIZABLEisolation, we’d need to look for read-write conflicts here instead, where other concurrent transactions wrote rows (or predicates) that we read. Reads are significantly more common than writes in OLTP workloads (especially poorly optimized ones that do any scans), and so these conflicts are more common. This is the root of the difference in performance between the snapshot and serializable isolation levels in modern databases. - OCC is a technique for implementing transaction isolation that dates back to Kung and Robinson’s 1981 paper On Optimistic Methods for Concurrency Control, and has been used in a wide range of transaction systems since.

- Or attempt to write keys that a concurrent transaction has used

SELECT ... FOR UPDATEon. This is a subtle topic, which I’ll look at in detail in a future post.