About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

A Story About a Fish

In the 1930s, Marjorie Latimer was working as a museum curator in East London. Not the eastern part of London as one may expect. This East London is a small city on South Africa’s south coast, named so thanks to colonialism’s great tradition of creative and culturally relevant place names. Latimer was a keen and knowledgeable naturalist, and had a deal with local fishermen that they would let her know if they found anything unusual in their nets. One morning in 1938, she got a call from a fishing boat captain named Hendrik Goosen. He’d found something very unusual indeed, and wanted Marjorie to look at it. The fish which Hendrik Goosen showed Marjorie Latimer was truly unusual. Unlike anything she had seen before.

Latimer knew just the person to identify it: professor JLB Smith at Rhodes University in nearby Grahamstown (now Makhanda). He was away, so she had the unusual fish gutted and taxidermied, and sent sketches to the professor. He replied (in all-caps, following the fashion at the time):

MOST IMPORTANT PRESERVE SKELETON AND GILLS

Smith had immediately identified the fish as something well known to science. Many like it had been seen before. This one, however, was particularly surprising. It was alive, nearly 66 millions years after the last of its kin had been thought dead. Latimer had found a Coelacanth, a species of fish that had hardly evolved in the last 400 million years, and believed to exist only in the fossil record.

At the time, the Coelacanths were thought to be closely related to the Rhipidistia, which were thought to be an ancestor of all modern land-based vertebrates. The science on that topic has moved on, but Goosen’s chance find, combined with Latimer’s hard work in having it identified, created a special moment in the history of biology.

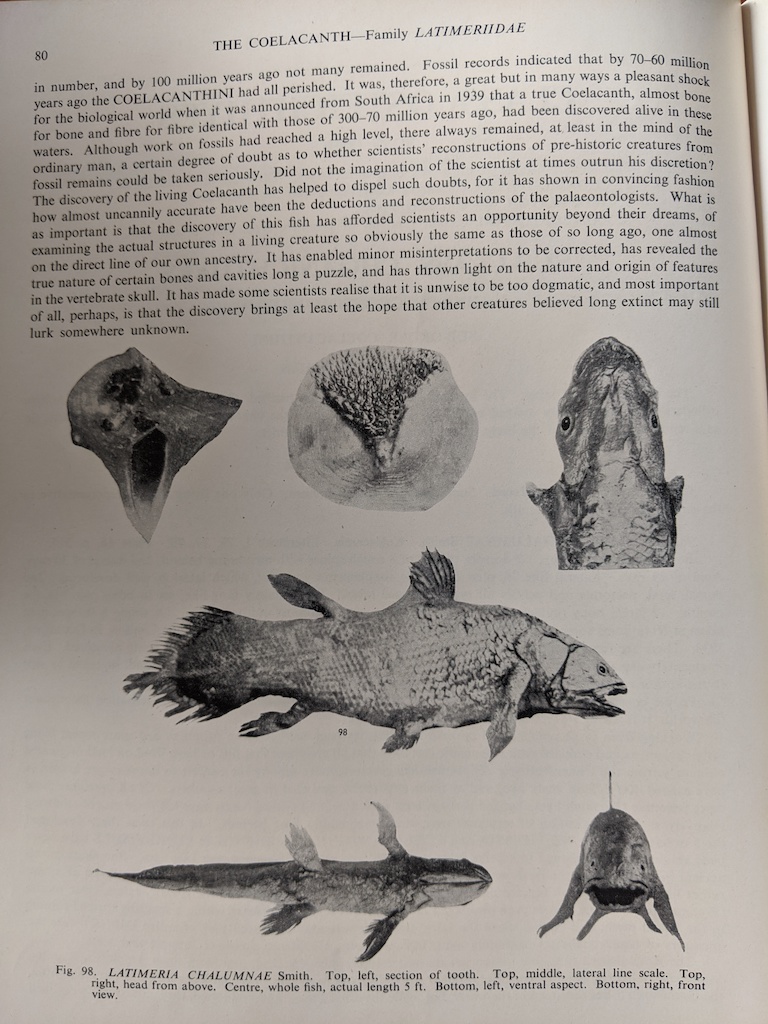

I was thinking about this story last night, because my daughter has been learning about Coelacanths at school. In the 1940s, JLB Smith and his wife Margaret wrote and illustrated a beautiful book called The Sea Fishes of Southern Africa. My grandmother studied biology at Rhodes during the time they were writing the book, and knew the Smiths and Marjorie Latimer. Margaret Smith gave her a signed copy of their book, sometime around 1950. I was fortunate to inherit the book, and share the Smiths description and drawings of the Coelacanths with my daughter.

I hadn’t opened The Sea Fishes of Southern Africa in ten years, but re-reading Smith’s description of it was like a visit with my late grandmother. She never failed to share her excitement about, and appreciation for, all living things. I vividly remember her telling the Coelacanth story, and her small part in it, sharing the wonder of discovery and the importance of paying attention to the things around us. You never know when you’ll learn something new. Perhaps, as the Smiths write, it is unwise to be too dogmatic.

Update Ross Goosen, grandson of Hendrik P Goosen the captain of the I & J trawler Nerine,who in 1938 caught the original Coelacanths off East London reached out to say:

A lot is always made about JLB Smiths contribution to the ‘Old four legs’ story,but if my grandfather had not used his experience of all those years at sea and had not contacted Marjorie Latimer about the strange fish that he had just caught,then the world would still be in the dark about the existence of this prehistoric fish.