About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

False Sharing versus Perfect Placement

This is part 3 of an informal series on database scalability. The previous parts were on NoSQL, and Hot Keys.

In the last installment, we looked at hot keys and how they affect the theoretical peak scale a database can achieve. Hidden in that post was an underlying assumption: that can successfully isolate the hottest key onto a shard of its own. If the key distribution is slow moving (hot keys now will still be hot keys later) then this is achievable. The system can reshard (for example by splitting an merging existing shards) until heat on shards are balanced.

Unfortunately for us, this nice static distribution of key heat doesn’t seem to happen often. Instead, what we see is that popularity of keys changes over time. Popular products come and go. Events come and go. The 1966 FIFA world cup came and went1. If the distribution of which keys are popular right now changes often enough, then moving around data to balance shard heat becomes rather difficult and expensive to do.

Even Sharding and False Sharing

At the extreme end, where there is no stability in the key heat distribution, we may not be able to shard our database better than evenly (or, somewhat equivalently, randomly). This might work out well, with the hottest key on one shard, the second hottest on another, third hottest on another, and so on. It also might work out poorly, with the hottest and second hottest keys on the same shard. This leads to a kind of false sharing problem, where shards are hotter than they strictly need to be, just by getting unlucky.

How likely are we to get unlucky in this way?

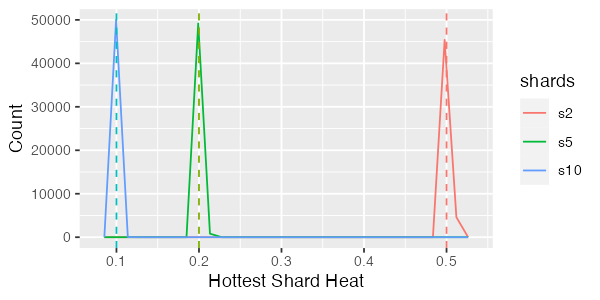

Let’s start with uniformly distributed keys, and think about a database with 10,000 keys, sharded into 2, 5 or 10 different shards. Ideally, for the 2 shard database we’d like to see the hottest shard get 50% of the traffic. For the 10 shard database 10%. This is what the distribution looks like with 50,000 simulation runs (solid lines are simulation results, dotted vertical lines show ‘perfect’ sharding)2:

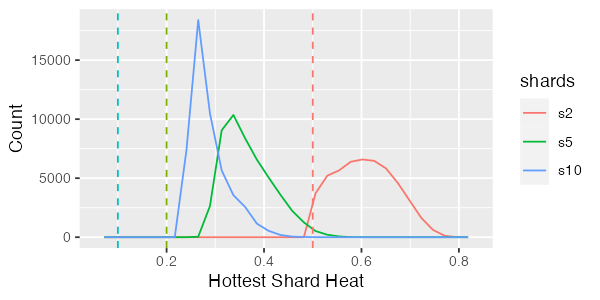

Not bad! In fact, with nearly all the simulation runs hitting the ideal bound, we can safely say that we don’t have a major false sharing problem here. Uniform, however, is easy mode. What about something a little more biased, like the Zipf distribution. This is what things look like for Zipf distributed keys:

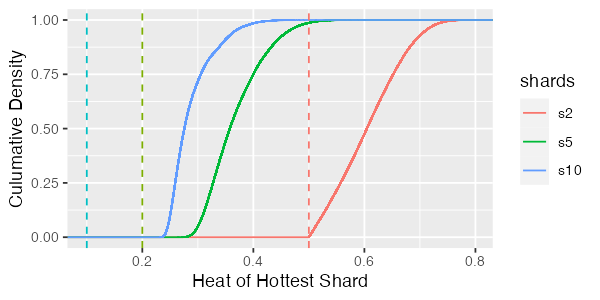

Ah, that’s much worse. We can see that there are some runs for the two-shard case where the hottest shard is getting nearly 80% of the database traffic! Even for the 10 shard case, the hottest shards are still getting over 40% of database traffic, compared to the ideal 10%. Let’s look at the cumulative version to get a feeling for how common this is.

Here, for example, we can see in the 5 shard case that nearly 15% of the time the hottest shard is getting double the traffic we would ideally expect.

The Trend

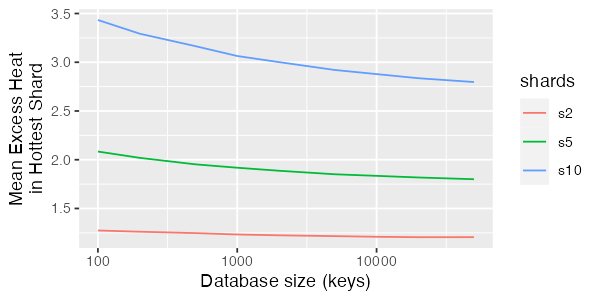

My instinct, when I started looking at the simulation results, is that the amount of false sharing would decrease significantly as the database size gets larger, because there would be more “dilution” of the hot keys. Defining the amount of false sharing as the mean hot shard load divided by the ideal shard load, this is exactly what we see happen:

However, this drop is relatively slow, and so doesn’t save us from the underlying problem until database sizes become very big indeed, and size never truly solves the problem. But this is still one of those luxury problems where scale makes things (slightly) easier.

Does it matter?

Whether this false sharing effect is important or not depends on other factors in your system architecture. It may, however, be surprising when sharding is not as effective as we may have hoped. For example, if we split the database in half and get an 80:20 split rather than the expected 50:50 split, we might need to split further and into smaller shards that would have otherwise been ideal.

This doesn’t only affect databases. The same effect will happen with sharded microservices, queues, network paths, compute hardware, or whatever else. In all these cases, this effect is practically important because it makes uniform or random sharding significantly less effective than it might be (and so require more elaborate sharding approaches), and might make sharding much less effective for heat distributions that are highly variable.

Temporal and Spatial Locality

The distributions above assume that the heat is spread out over the key space evenly, and not in a way that is aligned with the sharding scheme.

For example, consider a database table with an SERIAL or AUTO_INCREMENT primary key, and the common pattern that recently-created rows tend to be accessed more often than older rows (customers are more likely to check on the status of recent orders, or add additional settings to new cloud resources, etc). If the sharding scheme is based on key ranges, all this heat may be focused on the shard that owns the range of most recent keys, leading to even worse shard heat distributions than the simulations above. Schemes with shard based on hashes (or other non-range schemes) avoid this problem, but introduce other problems by losing what may be valuable locality.

Footnotes

- Don’t tell the English. If they ask you about it, tell them it’s still the most important sporting event in history, then run.

- You can check out the simulation code on GitHub if you want to check my work, or try different distributions for yourself.