About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

Hot Keys, Scalability, and the Zipf Distribution

Does your distributed database (or microservices architecture, or queue, or whatever) scale? It’s a good question, and often a relevant one, but almost impossible to answer. To make it a meaningful question, you also need to specify the workload and the data in the system. Given this workload, over this data, does this database scale?

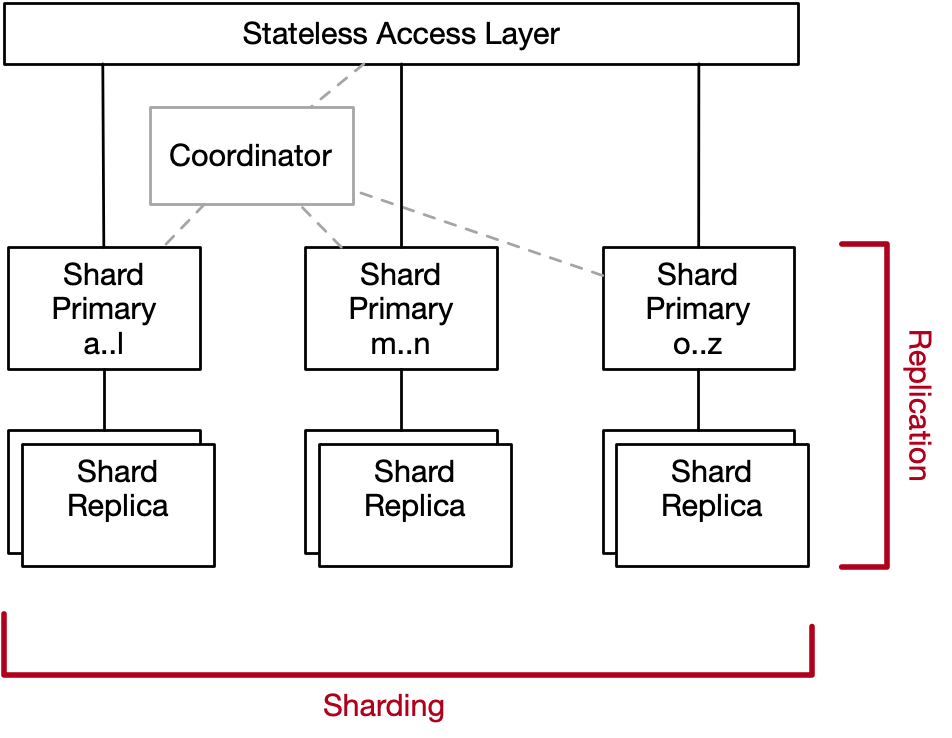

One common reason systems don’t scale is because of hot keys or hot items: things in the system that are accessed way more often than the average thing. To understand why, lets revisit our database architecture from the previous post:

Sharding, the horizontal dimension in this diagram, only works if the workload is well distributed over the key space. If some keys are too popular or too hot, then their associated shard will become a bottleneck for the whole system. Adding more capacity will increase throughput for other keys, but the hottest ones will just experience errors or latency. In this post, we’ll look at some examples to understand how much of a bottleneck this actually is.

Say hello to Olivia and Liam

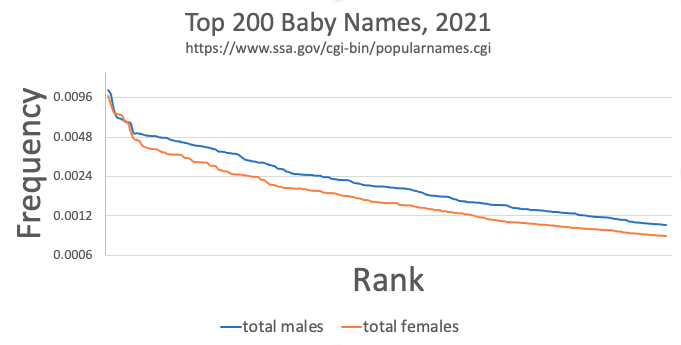

If you were born in the USA in 2021, there’s about a 1% chance your name is either Olivia or Liam1, or about a 0.01% chance your name is Blaise or Annabella. Baby names come in waves and fashions, and so some are always much more popular than others3.

Now, imagine we were using the baby’s first name as a database key. Clearly, that would skew accesses heavily towards Olivia’s partition, affecting throughput for the whole database. But how much of a practical concern is that effect?

Let’s start by building our intuition. For simplicity we’re going to consider just girls. We’d expect about 1% of babies to be called Olivia, and at least 1% of traffic then going to Olivia’s partition. So, if we’re trying to avoid errors or latency caused by overloading that partition, we’d expect that by the time the database was handling $\approx \frac{1}{0.01} = 100$ times the traffic Olivia’s partition can handle, then adding more shards won’t help.

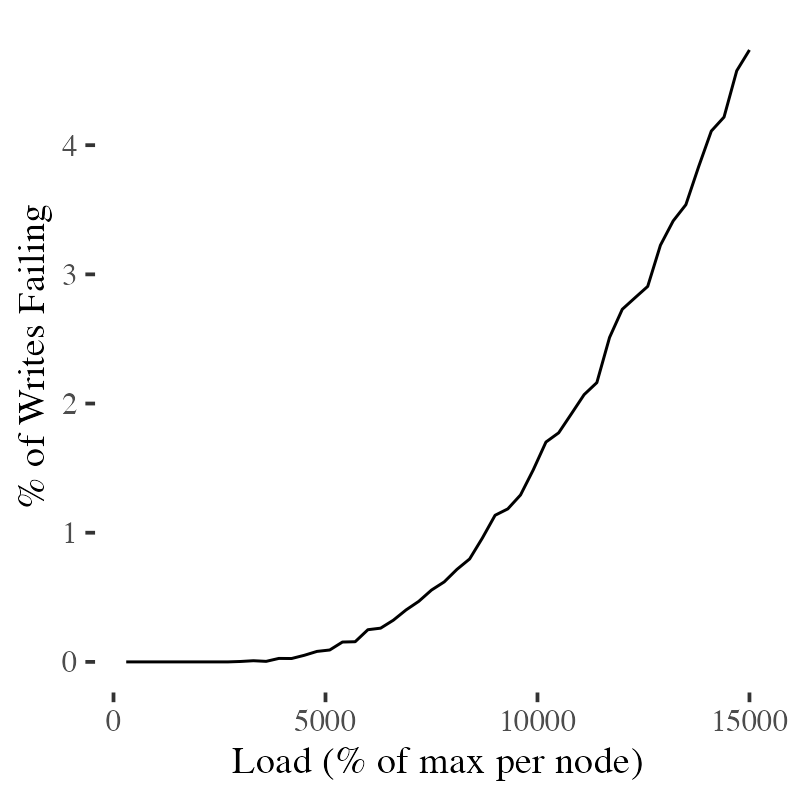

Unfortunately, that’s a very optimistic picture. Assuming that each incoming request is independently sampled from the names distribution, we run into a balls into bins problem2. Sometimes, by chance, the load on Olivia’s partition will exceed the limit earlier than expected, leading to overload earlier than expected. How often will this happen? Because I’m a coward and afraid of trying to reason about this in closed form, we’re going to simulate it, assuming that once there are too many requests in flight on a node then any more incoming will fail.

What we see is that errors start picking up a lot earlier than expected. Error start off at a low level around 50 nodes, and pick up rather quickly after that. The 100 we expected doesn’t even seem achievable.

Zipf Bursts Onto the Scene

The Zipf distribution (and power law distributions more generally, like the Zeta distribution), are used as canonical examples of skewed key distributions in database textbooks, papers, and benchmarks. This makes some sense, because some natural things like text word frequencies, are Zipf distributed. It doesn’t make that much sense, because it’s not clear how often those Zipf-distributed things are used as database keys anyway. City sizes, maybe.

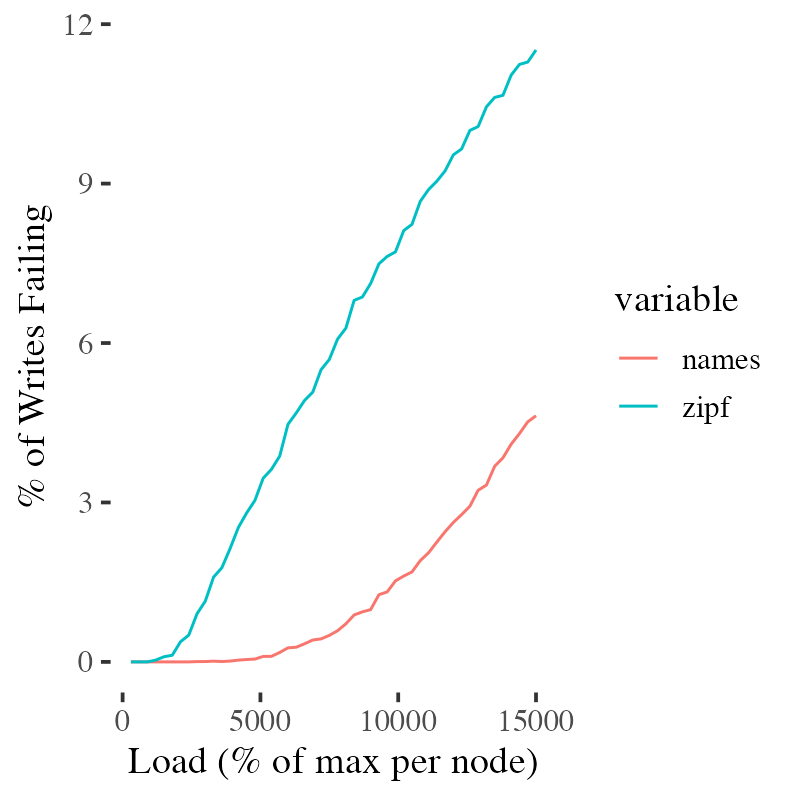

That aside, how does the Zipf distribution’s behavior differ from our baby names distribution? Zipf is very aggressive! Wikipedia says that the is 7% of all words in typical written English. We would expect a Zipf-distributed key space to scale even worse than the baby names. Picking the parameter $s = 0.7$ to represent typical adult English, and $N = 1000$ to match our database of baby names, we can see how much Zipf distributed data limits our scalability.

The errors take off much earlier here - once we’ve scaled to about 10 nodes - mostly driven by the nodes that own the and of. The important point here is that these scalability predictions are very sensitive to the shape of the distribution (especially at the head), and so using Zipf as a canonical skewed access distribution probably won’t reflect the results you’ll get on real data.

As a systems community, we need to get better at benchmarking with real distributions reflective of real workloads. Parametric approaches like Zipf do have their place, but they are very frequently (one might say too frequently) used outside that place.

Zipf at the Limit

Clearly, heavily skewed data affects error rates as the hottest nodes overheat. But does it strictly limit scalability? Is there a point where adding more shards will not allow any more throughput at any cost? There must be a limit when the number of shards exceeds the key cardinality, what if we assuming a Zipf distribution and infinite cardinality? Let’s look at the definition of the Zipf distribution:

\[f(k; s, N) = \frac{k\^{-s}}{\sum_{n=1}\^N \frac{1}{n\^s}}\]For $s \leq 1$, the Zipf distribution isn’t well defined with $N = \infty$. But, going back to our approximate analysis above, we can say that scale is roughly proportional to $\frac{1}{f(1; s, N)}$, which means that it is roughly proportional to $\sum\^N_{n=1} \frac{1}{n\^s}$, which grows rather quickly with $N$. That’s some good news!

What about the case where $s > 1$? Here, we have a nice, closed-form solution, since:

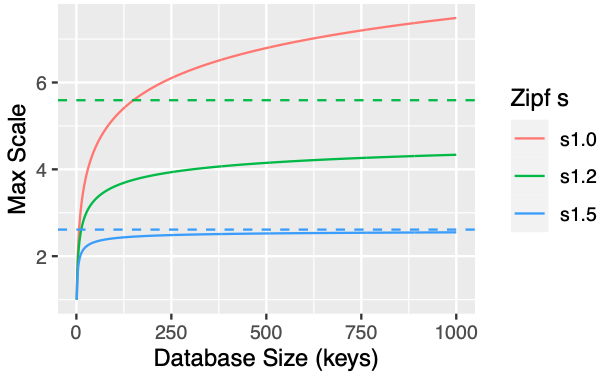

\[\sum_{n=1}\^\infty \frac{1}{n\^s} = \zeta(s)\]Which is relatively easy to calculate. For example $\zeta(1.1) \approx 10.6$, and $\zeta(2.0) \approx 2.6$. Data that follows these very steep power laws makes very poor keys indeed! Here’s what the limits look like for some larger values of $s$.

The dashed lines show the ultimate limit: even with an infinitely large key space, if your keys are distributed this way you can’t beat those limits without unbounded error rates.

Footnotes

- And if you are, look out for Sebastian. He’s not who you think he is.

- I feel like this problem has been stalking me my entire career.

- A fair number of sources (including database papers and textbooks) use names as an example of Zipf-distributed (or otherwise powerlaw-distributed) data. Looking at this graph doesn’t seem to support that claim.