About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

Seven Years of Firecracker

Back at re:Invent 2018, we shared Firecracker with the world. Firecracker is open source software that makes it easy to create and manage small virtual machines. At the time, we talked about Firecracker as one of the key technologies behind AWS Lambda, including how it’d allowed us to make Lambda faster, more efficient, and more secure.

A couple years later, we published Firecracker: Lightweight Virtualization for Serverless Applications (at NSDI’20). Here’s me talking through the paper back then:

The paper went into more detail into how we’re using Firecracker in Lambda, how we think about the economics of multitenancy (more about that here), and how we chose virtualization over kernel-level isolation (containers) or language-level isolation for Lambda.

Despite these challenges, virtualization provides many compelling benefits. From an isolation perspective, the most compelling benefit is that it moves the security-critical interface from the OS boundary to a boundary supported in hardware and comparatively simpler software. It removes the need to trade off between kernel features and security: the guest kernel can supply its full feature set with no change to the threat model. VMMs are much smaller than general-purpose OS kernels, exposing a small number of well-understood abstractions without compromising on software compatibility or requiring software to be modified.

Firecracker has really taken off, in all three ways we hoped it would. First, we use it in many more places inside AWS, backing the infrastructure we offer to customers across multiple services. Second, folks use the open source version directly, building their own cool products and businesses on it. Third, it was the motivation for a wave of innovation in the VM space.

In this post, I wanted to write a bit about two of the ways we’re using Firecracker at AWS that weren’t covered in the paper.

Bedrock AgentCore

Back in July, we announced the preview of Amazon Bedrock AgentCore. AgentCore is built to run AI agents. If you’re not steeped in the world of AI right now, you might be confused by the many definitions of the word agent. I like Simon Willison’s take:

An LLM agent runs tools in a loop to achieve a goal.1

Most production agents today are programs, mostly Python, which use a framework that makes it easy to interact with tools and the underlying AI model. My favorite one of those frameworks is Strands, which does a great job of combining traditional imperative code with prompt-driven model-based interactions. I build a lot of little agents with Strands, most being less than 30 lines of Python (check out the strands samples for some ideas).

So where does Firecracker come in?

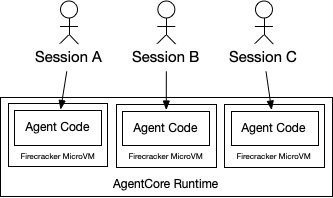

AgentCore Runtime is the compute component of AgentCore. It’s the place in the cloud that the agent code you’ve written runs. When we looked at the agent isolation problem, we realized that Lambda’s per-function model isn’t rich enough for agents. Specifically, because agents do lots of different kinds of work on behalf of different customers. So we built AgentCore runtime with session isolation.

Each session with the agent is given its own MicroVM, and that MicroVM is terminated when the session is over. Over the course of a session (up to 8 hours), there can be multiple interactions with the user, and many tool and LLM calls. But, when it’s over the MicroVM is destroyed and all the session context is securely forgotten. This makes interactions between agent sessions explicit (e.g. via AgentCore Memory or stateful tools), with no interactions at the code level, making it easier to reason about security.

Firecracker is great here, because agent sessions vary from milliseconds (single-turn, single-shot, agent interactions with small models), to hours (multi-turn interactions, with thousands of tool calls and LLM interactions). Context varies from zero to gigabytes. The flexibility of Firecracker, including the ability to grow and shrink the CPU and memory use of VMs in place, was a key part of being able to build this economically.

Aurora DSQL

We announced Aurora DSQL, our serverless relational database with PostgreSQL compatibility, in December 2024. I’ve written about DSQL’s architecture before, but here wanted to highlight the role of Firecracker.

Each active SQL transaction in DSQL runs inside its own Query Processor (QPs), including its own copy of PostgreSQL. These QPs are used multiple times (for the same DSQL database), but only handle one transaction at a time.

I’ve written before about why this is interesting from a database perspective. Instead of repeating that, lets dive down to the page level and take a look from the virtualization level.

Let’s say I’m creating a new DSQL QP in a new Firecracker for a new connection in an incoming database. One way I could do that is to start Firecracker, boot Linux, start PostgreSQL, start the management and observability agents, load all the metadata, and get going. That’s not going to take too long. A couple hundred milliseconds, probably. But we can do much better. With clones. Firecracker supports snapshot and restore, where it writes down all the VM memory, registers, and device state into a file, and then can create a new VM from that file. Cloning is the simple idea that once you have a snapshot you can restore it as many time as you like.

So we boot up, start the database, do some customization, and then take a snapshot. When we need a new QP for a given database, we restore the snapshot. That’s orders of magnitude faster.

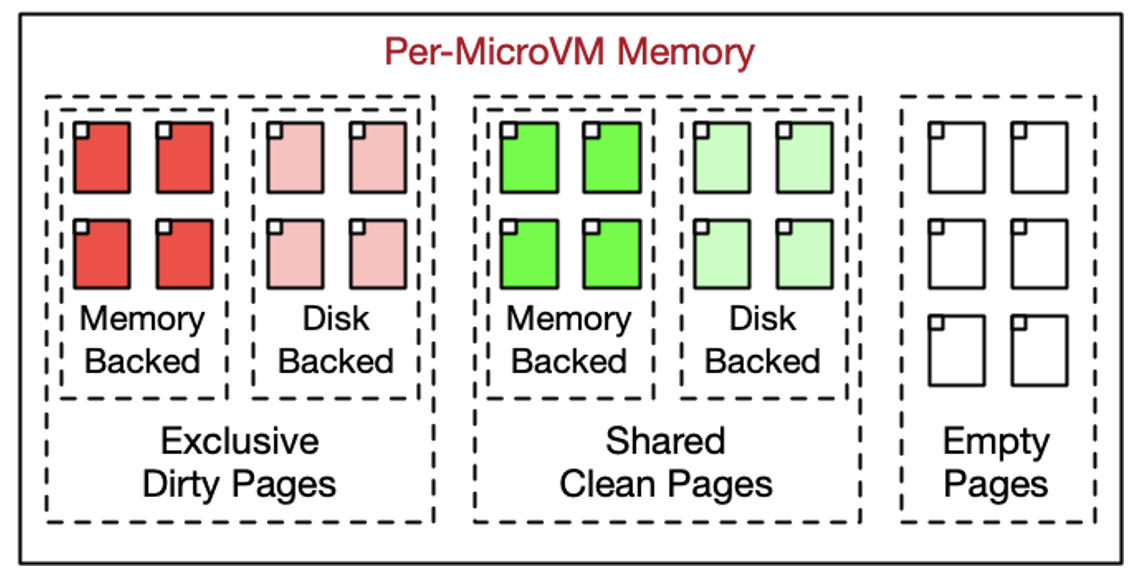

This significantly reduces creation time, saving the CPU used for all that booting and starting. Awesome. But it does something else too: it allows the cloned microVMs to share unchanged (clean) memory pages with each other, significantly reducing memory demand (with fine-grained control over what is shared).

This is a big saving, because a lot of the memory used by Linux, PostgreSQL, and the other processes on the box aren’t modified again after start-up. VMs get their own copies of pages they write to (we’re not talking about sharing writable memory here), ensuring that memory is still strongly isolated between each MicroVM. Another knock-on effect is the shared pages can also appear only once in some levels of the CPU cache hierarchy, further improving performance.

There’s a bit more plumbing that’s needed to make some things like random numbers work correctly in the cloned VMs2.

Last year, I wrote about our paper Resource management in Aurora Serverless. To understand these systems more deeply, let’s compare their approaches to one common challenge: Linux’s approach to memory management.

At a high level, in stock Linux’s mind, an empty memory page is a wasted memory page. So it takes basically every opportunity it can to fill all the available physical memory up with caches, buffers, page caches, and whatever else it may think it’ll want later.

This is a great general idea. But in DSQL and Aurora Serverless, where the marginal cost of a guest VM holding onto a page is non-zero, it’s the wrong one for the overall system. As we say in the Aurora serverless paper, Aurora Serverless fixes this with careful tracking of page access frequency:

− Cold page identification: A kernel process called DARC [8] continuously monitors pages and identifies cold pages. It marks cold file-based pages as free and swaps out cold anonymous pages.

This works well, but is heavier than what we needed for DSQL. In DSQL, we take a much simpler approach: we terminate VMs after a fixed period of time. This naturally cleans up all that built-up cruft without the need for extra accounting. DSQL can do this because connection handling, caching, and concurrency control are handled outside the QP VM.

In a lot of ways this is similar to the approach we took with MVCC garbage collection in DSQL. Instead of PostgreSQL’s VACUUM, which needs to carefully keep track of references to old versions from the set of running transactions, we instead bound the set of running transactions with a simple rule (no transaction can run longer than 5 minutes). This allows DSQL to simply discard versions older than that deadline, safe in the knowledge that they are no longer referenced. Simplicity, as always, is a system property.

Footnotes

- I might quibble with the use of LLM here, because it excludes agents that are based on models of different sizes, modes, and architectures. But that’s a minor point. What’s important is the tools and the loop.

- There’s more detail, some out of date, in our paper Restoring Uniqueness in MicroVM Snapshots.