About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

Resource Management in Aurora Serverless

My favorite thing about distributed systems is how they allow us to solve problems at multiple levels: single process problems, single machine problems, multi-machine problems, and large-scale cluster problems. Our new paper Resource management in Aurora Serverless1 describes what this looks like in context of a large-scale running system: Amazon Aurora Serverless.

What is Aurora Serverless?

Aurora Serverless (or, rather, Aurora Serverless V2 for reasons the paper explains) allows Amazon Aurora databases to scale in place as their workload changes, reducing costs, simplifying operations, and improving performance for customers with cyclical, seasonal, or organically growing workloads.

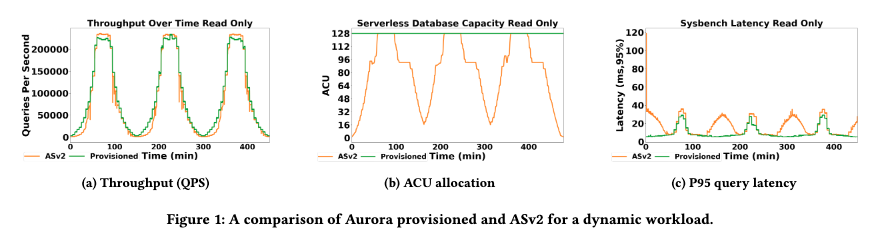

Here’s one example of what that looks like:

Notice how the size of the database (ACU allocation) grows and shrinks with the workload. It does that without disrupting connections, while transactions are running, and while keeping all session state. In this example there is some latency impact, but its small compared to what would have been achievable with manual scaling (and even smaller than the impact of having an under-sized database for the peaks).

Managing memory is what makes this a truly interesting systems problem. Traditional relational database engines are highly dependent on high local cache hit rates for performance. Aurora is slightly less so, but having the core working set3 in cache is still important for good OLTP performance. Working sets grow and shrink, and change, with changing access patterns. Scaling a database while offering good performance requires a careful and deep understanding of the size and occupancy of working sets, and careful management to ensure that the optimal amount of memory is available to store them.

Lowest Level: Hypervisor, Kernel, and DB Engine

By default, both Linux and database engines like Postgres and MySQL have a hungry hungry hippo approach to memory management: they assume that the marginal cost of converting a free memory page to a full one is zero, and the marginal value of keeping data in memory is slightly above zero. So they eat all the memory available to them. That makes a lot of sense: in a traditional single-system deployment these assumptions are true - there is no value in keeping memory free.

In an auto-scaling setting, however, this isn’t true. Memory is a significant driver of the cost of a database instance, and so to meaningfully scale-down we need to convince the database engine and kernel to release memory that is providing little value. In other words, during down-scaling, the marginal cost of memory tends to rise above the marginal value of keeping infrequently-used data2. To make this work, the team had to teach the database engines to give back memory (and to keep better track of which memory was providing value), teach the hypervisor to accept memory back from the guest kernel, and leverage Linux’s DAMON to keep track of guest pages that can be returned.

This co-optimization of database engine, kernel, and hypervisor is one of the most exciting things about the project for me. As we say in the paper, we’d love to see more research into this area:

Aurora Serverless evolution offers a powerful illustration of being able to evolve hypervisors and OS kernels in ways that make them better suited for DB workloads. This seems to be an under-tapped area of research, and there may be a lot of opportunity in co-designing and co-optimizing these layers.

Middle Level: On-Host Resource Management

Aurora Serverless packs a number of database instances onto a single physical machine (each isolated inside its own virtual machine using AWS’s Nitro Hypervisor). As these databases shrink and grow, resources like CPU and memory are reclaimed from shrinking workloads, pooled in the hypervisor, and given to growing workloads. The system needs to avoid running out of resources to give to growing workloads: running out of CPU means higher latency, and running out of memory can cause stability issues.

To avoid this condition, the local per-instance decider controls how quickly workloads can scale up and down, and what their optimal scaling targets are.

Top Level: Cluster-Level Resource Management

Cluster-level resource management is where the real cloud magic happens. With a large number of databases under our control, and a large fleet over which to place them, we can place workloads in a way that optimizes performance, cost, and utilization. When we first started this project, I borrowed the analogy of heart health4 to talk about the levels of control we have:

- Diet and Exercise We place workloads in a way that mixes workloads that are likely to grown and shrink at different times (decorrelation), provide a broad mix of behaviors and sizes (diversity), and mixes well-understood established workloads with a lot of scaling history with newer less-known ones. If we do this well enough, the job is almost done.

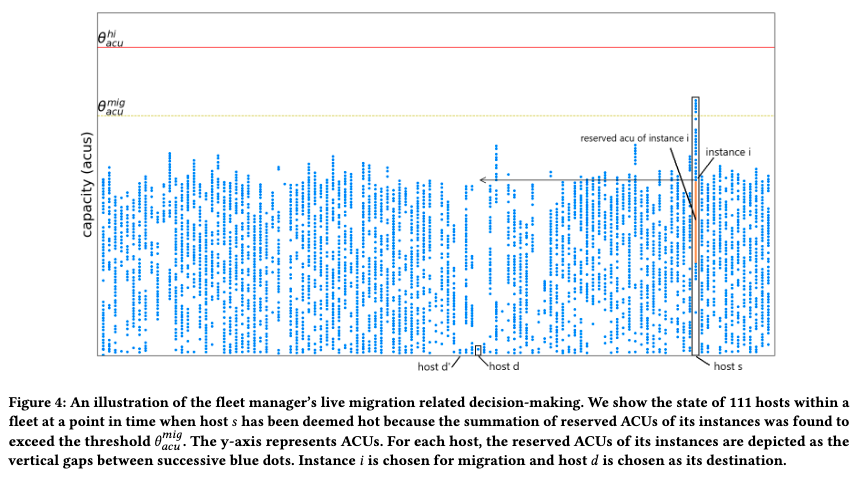

- Statins When one host is running too hot, and its resources are too low to provide a great customer experience, we live migrate one or more workloads elsewhere in the fleet. Live migration is seamless from a customer perspective, but a lot of data motion, so we try avoid it when we can.

- Surgery When local resources are running low, deciders and policy may limit the growth of one or more workloads, ensuring stability for those workloads and the system overall. Surgery may be life-saving and necessary, but is a situation best avoided.

This is more-or-less how Aurora Serverless V2’s resource management at the cluster level works: a mix of smart placement, live migration, and local limits when absolutely needed. Here’s an example from the paper:

To get an idea of how effective the diet and exercise step is, here’s some data from the paper:

Collectively, these instances exhibited 16,440,024 scale-up events. Of these, only 2,923 scale-up events needed one or more live migrations … while the vast majority (99.98%) were satisfied completely via our in-place scaling mechanism.

Live migration, the ability to move a running VM from one physical host to another, is another great example of innovation across multiple levels of the system. The mechanism of live migration is an extremely low-level one (down to the point of copying CPU registers over the network), but the policy of when to apply it in Aurora Serverless can only be made well at the large-scale cluster level.

Broader Lessons

One section of systems papers I often flip to first is the key take aways or lessons learned sections. There are a few in ours that seem worth highlighting:

Designing for a predictable resource elasticity experience has been a second central tenet … on occasion, we do not let an instance grow as fast as the available headroom on its host would theoretically allow.

Database customers love performance, and love low cost. But, perhaps more than anything else, they love predictability. Optimizing for predictable performance, even when it means leaving absolute scalability on the table, isn’t the best thing for benchmarks but we believe it’s what our customers want.

We found it effective to have the fleet-wide vs. host-level aspects of resource management operate largely independently of each other. … This significantly simplifies our resource management algorithms and allows them to be more scalable than the alternative.

This, again, is a case where we’re leaving potential absolute performance on the table to optimize for another goal. In this case, to optimize for simplicity. More directly, this decision allowed us to optimize for static stability: the vast majority of scale needs can still be met even when the cluster-wide control plane is unavailable. This is the kind of trade-off that system designers face all the time: making globally optimal decisions is very attractive, but requires that decisions degrade when the global optimizer isn’t available or can’t be contacted.

Conclusion

Please check out our paper Resource management in Aurora Serverless. It goes into a lot more detail about the system and how we designed it, and the interesting challenges of teaching traditional database engines to scale. This was a super fun project to work on, with an extremely talented group of people. We’re super happy with how customers have received Aurora Serverless V2, and the team’s working every day to make it better.

Footnotes

-

Our paper will appear at VLDB later this year. The Authors are Bradly Barnhart, Marc Brooker, Daniil Chinenkov, Tony Hooper, Jihoun Im, Prakash Chandra Jha, Tim Kraska, Ashok Kurakula, Alexey Kuznetsov, Grant McAlister, Arjun Muthukrishnan, Aravinthan Narayanan, Douglas Terry, Bhuvan Urgaonkar, and Jiaming Yan. As with most papers we write at AWS, the authors are listed in alphabetical order.

-

This marginal costs mental model comes from Gray and Putzolu’s 1984 classic Five Minute Rule paper, which provides a crisp mental model for thinking about the value and cost of marginal pages in a database system.

-

Did you know that the idea of a working set dates back to 1968? Denning’s The Working Set Model for Program Behavior lays out the idea that programs have a set of data they work on most frequently, and keeping that data around in memory improves performance.

-

I think I heard this first from David R. Richardson when he was running the AWS Lambda team, but my memory is hazy.