About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

Let’s Consign CAP to the Cabinet of Curiosities

Brewer’s CAP theorem, and Gilbert and Lynch’s formalization of it, is the first introduction to hard trade-offs for many distributed systems engineers. Going by the vast amounts of ink and bile spent on the topic, it is not unreasonable for new folks to conclude that it’s an important, foundational, idea.

The reality is that CAP is nearly irrelevant for almost all engineers building cloud-style distributed systems, and applications on the cloud. It’s much closer to relevant for developers of intermittently connected mobile and IoT applications, and space where the trade-off is typically seen as common sense already.

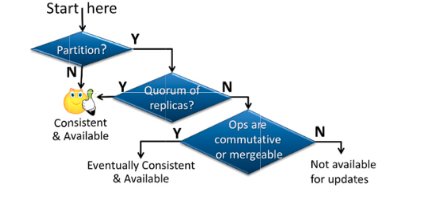

We’ll start with this excellent diagram from Bernstein and Das’s Rethinking Eventual Consistency:

CAP interests itself in the first two boxes. If there’s no partition (everybody can speak to everybody), we’re OK. Where CAP goes off the rails is the second box: if a quorum of replicas is available to the client, they can still get both strong consistency, and uncompromised availability.

What do we mean when we say Available?

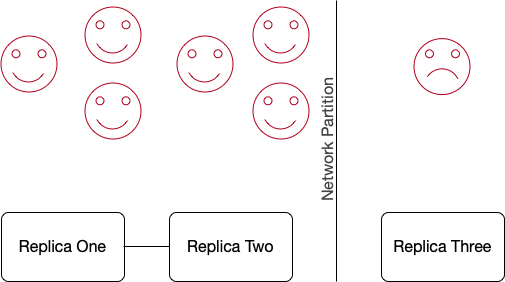

Consider the quorum system below. We have seven clients. Six are on the majority (quorum1) side, and are smiling because they can enjoy both availability and strong consistency (provided the system doesn’t allow the seventh client to write). The frowning client is out in the cold. They can get stale reads, but can’t write, so they’re frowning.

The formalized CAP theorem would call this system unavailable, based on their definition of availability:

every request received by a non-failing node in the system must result in a response.

Most engineers, operators, and six of seven clients, would call this system available. This difference in definitions for a common everyday term causes no end of confusion. Including among those who (incorrectly) claim that this system can’t offer consistency and availability to the six happy clients. It can.

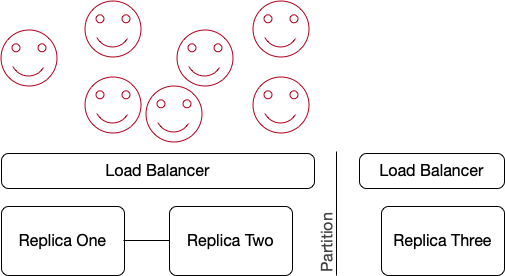

Can we make the seventh client happy?

As system operators, we still don’t love this situation, and would like all seven of our clients to be happy. This is where we head down to the third box in Bernstein and Das’s diagram, which gives us two choices.

- We can accept writes on both sides, provided those writes can be merged later in a sensible way, and offer eventually-consistent reads on both sides.

- We can find another way to make the seventh client happy.

The majority of the websites and systems you interact with day-to-day take the second path.

Here’s how that works:

Seven happy clients talk to our service via a load balancer. DNS, multi-cast, or some other mechanism directs them towards a healthy load balancer on the healthy side of the partition. The load balancer directs traffic to the healthy replicas, from that healthy side. None of the clients need to be aware that a network partition exists (except a small number who may see their connection to the bad side drop, and be replaced by a connection to the good side).

If the partition extended to the whole big internet that clients are on, this wouldn’t work. But they typically don’t.

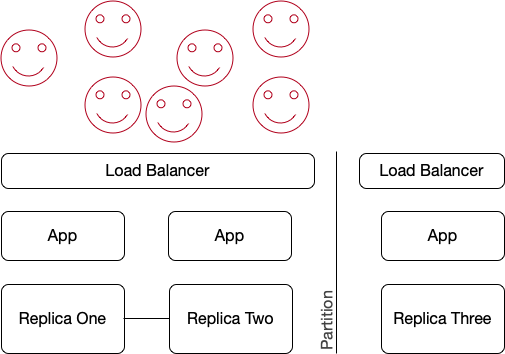

Extending to Architectures On the Cloud

Architectures in the cloud, or in any group of datacenters, do need to deal with network partitions an infrastructure failures. They do that using the same mechanism.

Applications are deployed in multiple datacenters. A combination of load balancer and some routing mechanism (like DNS) directs customers to healthy copies of the application that can get to a quorum of replicas. Clients are none the wiser, and all have a smile on their faces.

The CAP Theorem is Irrelevant

The point of these simple, and perhaps simplistic, examples is that CAP trade-offs aren’t a big deal for cloud systems (and cloud-like systems across multiple datacenters). In practice, the redundant nature of connectivity and ability to use routing mechanisms to send clients to the healthy side of partitions means that the vast majority of cloud systems can offer both strong consistency and high availability to their clients, even in the presence of the most common types of network partitions (and other failures).

This doesn’t mean the CAP theorem is wrong, just that it’s not particularly practically interesting.

It also doesn’t mean that there aren’t interesting trade-offs to be considered. Interesting ones include trade-offs between on-disk durability and write latency, between read latency and write latency, between consistency and latency, between latency and throughput, between consistency and throughput2, between isolation and throughput, and many others. Almost all of these trade-offs are more practically important to the cloud system engineer than CAP.

When is CAP Relevant?

CAP tends to be most relevant to the folks who seem to talk about it least: engineers designing and building systems in intermittently connected environments. IoT. Environmental monitoring. Mobile applications. These tend to be cases where one device, or a small group of them, can be partitioned off from the internet mother ship due to awkward physical situations. Like somebody standing the way of the laser. Or power failures. Or getting in an elevator.

In these settings, applications simply must visit the bottom right corner of Bernstein and Das’s diagram. They must figure out whether to accept writes, and how to merge them, or they must be unavailable for updates. It’s also worth noting that these applications tend not to contain full replicas of the data set, and so read availability may also be affected by loss of connectivity.

I suspect that these folks don’t think about CAP for the same reason you don’t think about air: it’s just part of their world.

What About Correctness?

My point here isn’t that you can ignore partitions. Network partitions (and other kinds of failures) absolutely do happen. Systems need to be designed, and continuously tested, to ensure that their behavior during and after network partitions maintains their contract with clients. That contract will likely include isolation, consistency, atomicity, and durability promises. Once again, the trade-off space here is deep, and CAP’s particular definition of correctness (linearizability3) is both too narrow to be generally useful, and likely not the criterion that is going to drive the majority of design decisions. Similarly, network partitions are only one part of a good model of failures. For example, they don’t capture re-ordering or multi-delivery of messages, both of which are important to consider in both protocols and implementations.

CAP is both an insufficient mental model for correctness in stateful distributed systems, and not a particularly good basis for a sufficient model.

A challenge

The point of this post isn’t merely to be the ten billionth blog post on the CAP theorem. It’s to issue a challenge. A request. Please, if you’re an experienced distributed systems person who’s teaching some new folks about trade-offs in your space, don’t start with CAP. Maybe start by talking about durability versus latency (how many copies? where?). Or one of the hundred impossibility results from this Nancy Lynch paper. If you absolutely want to talk about a trade-off space with a cool acronym, maybe start with CALM, RUM, or even PACELC.

Let’s consign CAP to the cabinet of curiosities.

Footnotes

-

In this post, I’m going to use majority and quorum interchangeably, despite the fact that some systems have quorums that are not majorities. The predominant case is that quorum is a simple majority.

-

The Anna Key-Value store from Chenggang Wu and team at Berkeley is one great example of an exploration of a trade-off space.

-

I have no beef with linearizability. In fact, if you haven’t read Herlihy and Wing you should do that. The point isn’t that linearizability isn’t useful, it’s that it’s only a local property of single objects (see Section 3.1 of the paper).