About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

Pat’s Big Deal, and Transaction Coordination

I have a lot of opinions about Pat Helland’s CIDR’24 paper Scalable OLTP in the Cloud: What’s the BIG DEAL?1. Most importantly, I like the BIG DEAL that he proposes:

Scalable apps don’t concurrently update the same key.

Scalable DBs don’t coordinate across disjoint TXs updating different keys.

In exchange for fulfilling their sides of this big deal2 the application gets a database that can scale6, and the database gets a task to do that allows it to scale. The cost of this scalability, for the application developer, is having to deal with a weird concurrency phenomenon called write skew. In this post, we’ll look at write skew, why not preventing it helps databases scale, and how we can alter Pat’s big deal to prevent write skew and get serializability.

In particular, we’ll try answer two big questions:

- Is Pat’s big deal the best deal available?

- Would a serializable big deal be better for application programmers?

Snapshot Isolation

The big deal experiences write skew because of the database isolation level that Pat chose: snapshot isolation. Other than this particular weird behavior, the application can pretend that concurrent transactions run in a serial total order, which makes application developer’s lives easy. Nobody likes reasoning about concurrency, and reasoning about concurrency while correctly implementing business logic is pretty hard, so that’s comforting.

There are a lot of ways to talk about these concurrency anomalies in the database literature. Tens, at least. The one I think is most accessible to developers is Martin Kleppmann’s Hermitage, a set of minimal tests that illustrate each of the weird things that databases users can experience.

The test setup is super simple:

create table test (id int primary key, value int);

insert into test (id, value) values (1, 10), (2, 20);

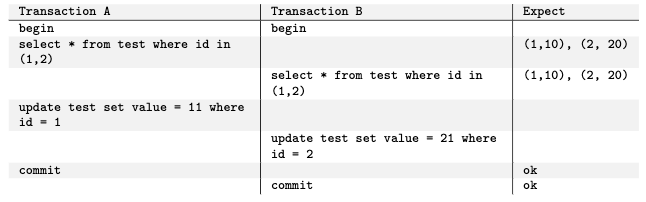

Next, we make two connections to the database we’ll call A and B, and run a transaction through each connection. For each row of the table, imagine us running that statement, waiting for it to end, and then going on to the next row.

In a snapshot isolated database, both A and B commit. In a serializable database, one of them needs to fail: there’s no way to order these two transactions into a serial order that makes sense (either A needs to see B’s writes, or B needs to see A’s)3.

This isn’t some strange academic edge case. For example, consider an application that reads from the stuff in warehouse table, then writes to an order table (without updating the warehouse, because the stuff is still there). The snapshot isolated version will sell some things too many times.

The big deal then comes with a real trade-off, and forces the application programmer to take some care to ensure correct results (but, importantly, less so than at lower levels like read committed).

Is SI Ideal for the Big Deal?

To understand whether SI is ideal for the big deal, we need to look at another angle on isolation: what coordination the database needs to do to achieve that level4. Let’s say we have a transaction A, and that transaction starts at some time $\tau^A_s$ and commits at some time $\tau^A_c$. To offer transaction A snapshot isolation, we need to offer it two properties:

Promise $1$: A’s reads see all the effects of transactions that committed before A started (i.e. before $\tau^A_s$), and none of the effects of transactions that committed after.

Promise $2_{si}$: A can only commit if none of the keys it writes have been written by other transactions between A starts and when it commits (i.e. between $\tau^A_s$ and $\tau^A_c$).

There are many ways to implement these guarantees, but the implementation decisions aren’t particularly important here. What’s important is the coordination needed. There doesn’t appear to be any inherent reason that promise 1 (the read guarantee) requires any coordination at all. For example, A could be given its own read replica which is completely disconnected from the stream of updates for the duration. It’s the second step where coordination is required: either to block the other writers (write locks), prevent other from committing, or detect the writes at the time A comes to commit. All of those require coordinating with other writers, either continuously through the transaction or at commit time.

Now, let’s consider what the second promise would look like if we wanted to offer serializability to A (and therefore prevent that write skew anomaly we talked about earlier).

Promise $2_{ser}$: A can only commit if none of the keys it read have been written by other transactions between A starts and when it commits (i.e. between $\tau^A_s$ and $\tau^A_c$).

We’ve changed one word in the definition, but entered something of a rabbit hole. The snapshot version of Promise 2 only needs to coordinate on writes, and find write-write conflicts between transactions. It only needs to keep track of keys that are written, and talk to the machines that are responsible for detecting conflicts on those keys.

The serializable version, on the other hand, needs to track all the keys A read (and the keys A’s predicates could have read but didn’t see), and then look for writes from other transactions to those keys. This doesn’t seem that different, really, but is a practical problem because it’s very easy (and common) for applications to make those read sets very big. For example, imagine A does:

SELECT id FROM stock WHERE type = 'chair' ORDER BY num_in_stock DESC LIMIT 1;

In the serializable version of the promise, now every chair is in A’s read set. A will then need to conflict with any other transaction that writes to any chair row, even if it’s not the one that A picked7. If we sold just one chair of any type during the time A is running, the serializable version of A couldn’t commit. What’s worse, from the Big Deal’s perspective of thinking about scalability, is that A would need to coordinate with the machines that own all chairs. In a distributed database, that’s a lot of coordination!

In the snapshot version, A would only need to coordinate with the machines that own any chairs it touched. Like this:

UPDATE stock SET num_in_stock = num_in_stock - 1 WHERE id = 'the cool chair the customer chose';

The snapshot version of A would only need to coordinate with that one machine that owns that one critical chair. Changing that one word between Promise $2_{si}$ and Promise $2_{ser}$ significantly changed the required coordination patterns.

But does that change the asymptotic scalability of the database? It does in this example (because of $O(\textrm{chairs})$ coordination for serializability and $O(1)$ for snapshot). But does it in general? Only if we believe that applications’ read behavior, in general, is asymptotically different from their write behavior (otherwise we’re just moving constants around5). Specifically, that the number of read-write edges is asymptotically different from the number of write-write edges in the data access graph.

This is the sense in which we can say that snapshot isolation is better for Pat’s Big Deal: making an assumption that applications access data in an asymptotically different way from how they write it.

I Am Altering the Deal

Wow, ok, that’s a lot of writing. But now I think we can propose, in the tradition of Roosevelt, a New Deal. A serializable deal. Without write skew. First, let’s remind ourselves about Pat’s Big Deal:

Scalable apps don’t concurrently update the same key.

Scalable DBs don’t coordinate across disjoint TXs updating different keys.

And now, our serializable New Big Deal.

Scalable apps don’t update keys that are frequently read by other concurrent processes, and try not to read keys that are frequently written.

As the kids say: Oof.

Scalable DBs don’t coordinate across disjoint TXs.

Well, we’ve simplified that one, but have made the definition of disjoint much more complex by defining it in terms of both reads and writes.

Pray I Don’t Alter it Any Further

The serializable version of the Big Deal is simpler for the application programmer from a correctness perspective. In fact, they can basically assume that concurrency doesn’t exist, which is very nice indeed. But it’s harder on the application programmer from a scalability and performance perspective, in that they have to be much more careful about the reads they do to get good scalability. It’s clear that’s not an easy win, but might be a net win in some circumstances.

Footnotes

- Also check out Murat Demirbas’s analysis of the paper.

- A big deal and a big deal. A major agreement, and very important.

- Hermitage separates this phenomenon into write skew (G2-item) and anti-dependency cycles (G2). They’re closely related, with the latter focusing on predicate reads.

- We’re skimming over some deep water here to make a point - isolation implementation is the topic of decades of database research, and decades of attempts to formalize (e.g. Adya, Crooks, et al), implement (e.g. Gray and Reuter, Kung and Robinson), and explain isolation levels. Please forgive me some simplification.

- But let’s be clear - in the actual practical world moving constants around is super important.

- In this post, I’m using the word scale (and related words like scalable and scalability) in the asymptotic sense Pat uses in his paper. Note that this is different from the sense that most folks use them in.

- Assuming A does any writes. If A is read-only, it can “commit” at $\tau^A_c = \tau^A_s$ (which, because of our Promise 1, is always a valid and serializable thing to do).