About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

What is Scalability Anyway?

What does scalable mean?

As systems designers, builders, and researchers, we use that word a lot. We kind of all use it to mean that same thing, but not super consistently. Some include scaling both up and down, some just up, and some just down. Some include both scaling on a box (vertical) and across boxes (horizontal), some just across boxes. Some include big rack-level systems, some don’t.

Here’s my definition:

A system is scalable in the range where the cost of adding incremental work is approximately constant.

I like this definition, in terms of incremental or marginal costs, because it seems to clear up a lot of the confusion by making scalability a customer/business outcome.

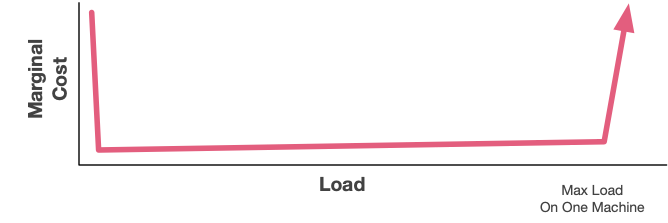

Let’s look at some examples, starting with a single-machine system. This could be a single-box database, an application that only runs on one server, or even a client-side application. There’s an initial spike in marginal cost (when you have to buy the box, start the instance, or launch the container), then a wide range where the marginal cost of doing more work is near-zero. It’s near-zero because the money has been spent already. Finally, there’s a huge spike in costs when the load exceeds what a single box can do - often requiring a complete rethinking of the architecture of the system.

The place people run into trouble with these single-box systems is either overestimating or underestimating the effect of that big spike on the right. If you’re too worried about it, you can end up spending a bunch of system complexity and cost avoiding hitting something that you’ll never actually hit. On the other hand, if you do hit it and didn’t plan for it, you’re almost universally going to have a bad time. We can’t grow the business until we rearchitect is a really bad place to end up.

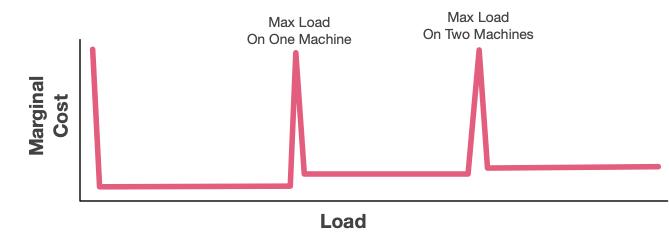

Our second example is a classic multi-machine architecture, which could be a sharded database, or a load-balanced application. As with a single box, we have an initial spike where we have to buy the first box/container/etc. Then there are periods where the marginal cost is low, with periodic spikes related to adding another fixed-size unit. Depending on the kind of application, the size of that initial spike may be the same size as the single-box case (some apps are trivial to load-balance), or it could be much higher (because you need to figure out how to shard).

This diagram is being very optimistic for sharded databases, essentially assuming the workload requires no cross-shard coordination. If it does, then the marginal costs once we pass a single machine are no longer constant, and there’s a significant stairstep as the need for coordination crosses more machines. I’ve written about this effect before.

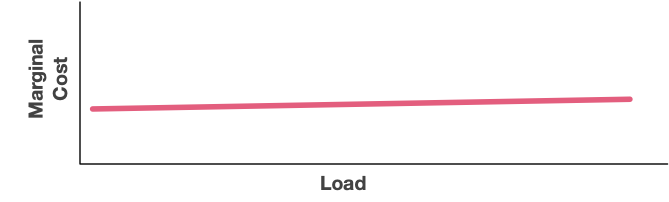

Our last example is a serverless system, like Lambda, or S3, or DynamoDB. In these models, the marginal cost of additional work (or additional storage) is nearly constant across the entire range. Work is billed per-unit, and if there are stair steps they’re usually downwards (as with S3’s tiered pricing).

This linearity of marginal cost is super important, and the key customer benefit of serverless pricing models. Scalability works both down (by not having an initial spike), and up (by not having spikes at particular loads). The downside is that the floor is a constant rather than being near-zero, which requires a fundamentally different approach to thinking about unit economics.

For this to work, you need to have a rather holistic view of cost. For example, you could achieve the serverless cost model, looking only at price, by using an existing serverless offering or by building your own. However, with a more realistic view of cost, building your own would come with a significant initial spike. All the cost to design, build, debug, etc the first version really adds up. The same is true of sharded or load balanced systems - their initial spikes tend to be larger. This is a key reason I prefer serverless as a base for systems building, where I can get it.

These examples aren’t anywhere near exhaustive. The definition, and this form of graphing it out, is a useful tool that I reach for all the time when thinking about system designs.