About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

On The Acoustics of Cocktail Parties

If you, like me, tend to practice punctual arrival at parties, you’ve likely noticed that most parties start out quiet. Folks are talking in small groups, using their normal voices, and having productive conversations. As more people arrive, the background noise increase. First a little, allowing guests to continue to use a conventional volume. Then, at some point, the background noise will exceed a normal speaking voice, and speakers will increase their volume. This doesn’t solve the problem: instead leading to a further increase in background noise and further volume increases.

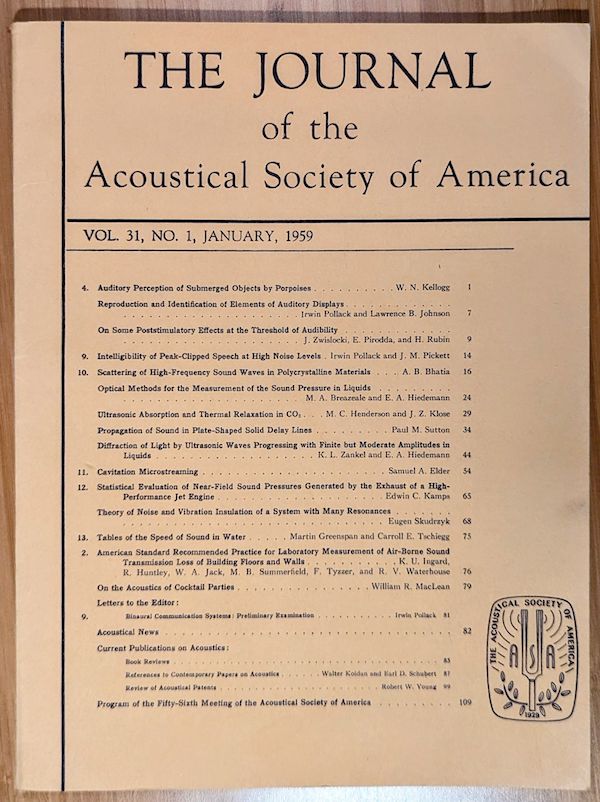

In 1959’s issue of the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America1, William R. MacLean6 modeled the root cause of this problem in a fun (and rather tongue-in-cheek) paper called On the Acoustics of Cocktail Parties2, 3.

In the article, MacLean models a party consisting of $N$ guests, clustered in groups of $K$. These guests, being well-mannered, only allow one speaker per group, for $\frac{N}{K}$ speakers.

In presence of a sufficiently weak background of noise, including other conversations, a well-mannered guest will talk with a small acoustic output $P_m$ … and, if necessary, will adjust his talking distance to a minimum conventional distance $d_0$.

This goes on until the background noise gets too loud:

In the presence of a gradually increasing background of noise however, the average guest $A$ will increase this talking power to a much larger value without being consciously aware of any strain or even the existence of the background, but at a certain maximum acoustic output $P_m$ the strain will become apparent to $A$ who, rather than overtax himself, will reduce his talking distance $d$ to to a distance less than the conventional minimum $d_0$ until conversation again becomes possible.

The mathematical model that MacLean builds is where this becomes interesting (and, I dare say, topical for this blog). First, he defines the critical distance $D$ at which the sound energy from each group’s speaker is equal to the background noise.

$D = \sqrt{\frac{\alpha V}{4 \pi h}}$

where $V$ is the volume of the room, $\alpha$ is the average sound absorption coefficient ($a < 1$), and $h$ mean free path of a ray of sound through the room4. Then he works out the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) that each listener observes:

$S^2 = \frac{ ( \frac{D}{d_0} )^2 + 1}{\frac{N}{K} - 1}$

Finally, introducing the minimum comfortable listener SNR $S_m$, we can calculate the critical number of guests $N_0$ where the party transitions from a quiet one (comfortable speaking in loose groups) to a loud one (shouting in uncomfortably tight groups).

$N < N_0 = K ( 1 + \frac{D^2 + d_0^2}{d_0^2 S_m^2} )$

MacLean goes on to show5 that even if the speakers are interrupted by silence (a speech from the host, perhaps), the party will become loud again in a finite time so long as $N \geq N_0$.

Why is this interesting?

These kinds of threshold effects are well known in all sorts of systems. In RFC 896 from 1984 John Nagle observes:

In heavily loaded pure datagram networks with end to end retransmission, as switching nodes become congested, the round trip time through the net increases and the count of datagrams in transit within the net also increases. This is normal behavior under load. As long as there is only one copy of each datagram in transit, congestion is under control. Once retransmission of datagrams not yet delivered begins, there is potential for serious trouble.

and

This condition is stable. Once the saturation point has been reached, if the algorithm for selecting packets to be dropped is fair, the network will continue to operate in a degraded condition.

Unlike MacLean’s cocktail party guests, RFC896’s TCP/IP endpoints can’t stand closer together (in the short term - they can in the longer-term by reconfiguring network topology), and instead need to be asked by the network itself to reduce the volume they are speaking at.

And, in Metastable Failures in Distributed Systems, Bronson et al say:

Metastable failures occur in open systems with an uncontrolled source of load where a trigger causes the system to enter a bad state that persists even when the trigger is removed.

MacLean’s cocktail parties exhibit this same phenomenon. When the number of guests exceeds $N_0$ and the party becomes loud, it is not sufficient for the number of guests to merely drop below $N_0$ for it to become quiet again. The background noise has become stuck in a high state, and only tapping a glass or a significant reduction in party goers is sufficient for the party to become quiet again.

Are Cocktail Parties Metastable?

It seems so, at least if we expand MacLean’s model slightly. First, consider that each group can improve their SNR $S^2$ (to keep $S^2 > S_m^2$) in two ways: increasing their speaking power $P$ or reducing their group diameter $d$. Our guests, being aware of each other’s personal space, will first respond to reduced noise (caused by lower $N$) by increasing $d$ (towards the minimal comfortable distance $d_0$) even if it means increasing their power $P$ (up to their maximum $P_m$). In this case, reducing $N$ below $N_0$ is not sufficient for the party to become quiet again once it has become loud (at least until $N$ is reduced far enough for $d_0$ to be reached and the social awkwardness of tight quarters to pass).

This is a bit of a stretch, but shows how relatively small details of these tipping point models can lead to behaviors that stick beyond the tipping point even when the stimulus is removed. I may take another look at this model using simulation in a later post.

Footnotes

- You can always rely on this blog to bring you the latest, most topical, research.

- I think I first learned about this paper on Dave Arnold’s Cooking Issues podcast, probably sometime around 2015.

- The internet would have us believe that cocktail parties were invented in 1917 (for, some, examples), but it seems likely that humans have enjoyed standing around in groups talking and drinking intoxicating fruity drinks for millennia. After all, wine dates back around 8000 years, and its hard to believe that everybody had the patience to wait for complete fermentation until the 20th century.

- Not being an acoustics expert, I’ll have to take MacLean’s word for this, but the calculation is very similar to how it would work out for radar, so I have no need for suspicion.

- MacLean’s method includes “Making the approximation of using differentials for finite differences”, the precise opposite of my usual approach.

- MacLean sounds like a fun person to know. According to his New York Times obituary, he was an early pioneer of ultrasound imaging, and did research in electronics, acoustics, electromagnetism, microwaves, satellite solar cells, the hazards of swimming‐pool lighting, radar, the defects of electric heating pads, electrical capacitators, optics, sound waves and the magnetic inspection of inaccessible pipes.