About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

The Four Hobbies, and Apparent Expertise

Around the end of high school, I started to get really into photography. My friend (let’s call him T) was also into it, which should have been great fun. But it wasn’t. Going shooting with him was never great, for a reason I didn’t figure out till much later. I wanted to take photos. T mostly enjoyed tinkering with cameras. As I’ve spent more time on different hobbies, it’s become clear that this is a common pattern. Every hobby, pastime1, or sport, is really four hobbies.

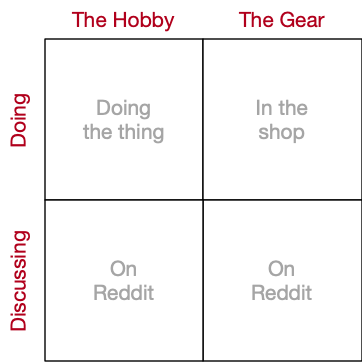

The first axis is doing versus talking, and the second is the hobby versus the kit. In nearly every case I’ve seen, people roughly sort themselves into one of these categories.

- Doing the thing. These are the folks who enjoy doing the actual activity: taking photos, skiing, golfing, hiking, hunting, whatever. You’ll find them out in the forest, on the slopes, or on the course.

- Collecting the kit. These folks enjoy collecting, maintaining, tuning, and fiddling with the kit. They tend to be attracted to kit-heavy hobbies like photography, but it seems like you can find them everywhere.

- Talking about the thing. This group enjoys discussing the activity. In-person, on forums, on Twitter, on Reddit, or anywhere else. They’ll talk technique, or pro competition, or about their day on the course.

- Talking about the kit. Like the previous group, these people enjoy the discussion. Instead of talking about the activity, they’ll talk about kit. Whether it’s if this season’s model is better than last’s, or the optimal iron temperature, they want to talk gear.

There’s some crossover between each of these categories, of course, but most communities and people primarily self-select into one of them. Outsiders unaware of this selection may come from the wrong quadrant, and chafe against the community before adapting or leaving.

But does it matter? It matters because the hobbies are more enjoyable, and the communities more welcoming and harmonious, if you pick which hobby you want to take part in. Say you want to pick up 3D printing, for example. You may go to a community and ask how to get started. This’ll send you down one of four paths: you could be encouraged to buy a printer you can start using right away, or could be encouraged to build your own from an online design, could be pulled into discussing the best filament, or the finer points of CoreXY vs bed slingers. If you want to make some stuff, three of these paths are likely to turn you off the hobby. Similarly, if you love to tinker, three won’t meet that need. And so on.

Once you’re established, you may find the hobby you enjoy and be able to tell the difference between communities. Or you may luck into the one you like. Often, though, you’ll feel like you’re in the wrong place and not sure why. When starting a hobby or sport, be sure to pick which of the four you want to take part in.

Kit heads will often say (or imply) that having the best kit leads to the best performance. That doesn’t seem true. I couldn’t ski the Lhotse Couloir even on the best gear ever made. My uncle would beat me at golf even if I had Tiger’s clubs and he just had my old 7 iron. That doesn’t mean that gear collecting and tweaking aren’t good hobbies, just that we need to be practical about the impact of gear on performance5.

Appearance of Expertise

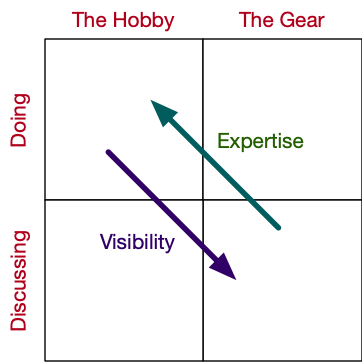

This breakdown matters for another reason, too, and extends beyond hobbies into our professional lives. It’s got to do with the appearance and visibility of expertise. Let’s assume for a moment that expertise primarily comes from experience. We’d expect the most experienced folks to be found in the top left quadrant: the practitioners. They could be practitioners of programming, of data analysis, or of leadership, but that’s where they would be found.

Which ones are the most visible? It’s the bottom two quadrants. The discussers, forum posters, Hacker News commenters, and serial conference speakers. If each person has a finite amount of time to spend either learning or sharing, we’d expect to find a negative correlation between output and experience. This, in turn, lowers the overall quality of content on any given subject2. As a second-order effect, communication is also a learned skill, so we might expect the ability to argue and persuade to also be negatively correlated with expertise (in that the arguer has spent their time learning to argue, at the cost of time spent developing expertise).

Kit and tools are another imperfect signal for expertise. Clearly, in our field, there’s a significant benefit to knowing a set of tools well, and being able to use these tools as an extension of our minds3. On the other hand, it is very easy to confuse the work of getting vim just-so with actual productivity, and the emacs expert as an expert on the larger field6. Observationally, I would say that there’s little correlation between expertise and kit-optimization in our field, positive or negative.

The lesson here is to be careful with the signals you use as proxies for competence. “Has the perfect Visual Studio config”, “has spoken at loads of conferences”, and “visible on Hacker News”4 seem like strong signals, when the reality seems to be that they are weak ones, at best.

Communication and Competence

I believe that one of the most important things an engineer or technical leader can do for their career is to practice, and develop, strong communication skills. It may seem like this belief is at odds with the point of this post. In some sense it is. Spending an entire career in that top-left quadrant is attractive to a lot of people (and fulfilling too). But being able to step out of it is valuable, and gives the opportunity to significantly increase impact and recognition.

So there’s a tension here, both for those looking to plot their career path, and for those looking to find experts to learn from. I don’t think its possible to entirely resolve this tension, but it is important to be thoughtful about it. Long-term, a mix is best. But I would say that, wouldn’t I?

Footnotes

- It even extends into other things that aren’t mere pastimes, like parenting.

- Academia is interesting here, because one could expect the same logic to apply. However, the incentives to write and share expertise there are explicit, at least somewhat correcting for this phenomenon.

- Too Heidegger?

- Or “has a blog”, like the one you’re reading.

- This even seems to apply in cases where the gear is doing more of the work. You don’t need to look around online long to find assertions about the importance of gear above all else, from no good software has ever been written in Java to it’s impossible to make useful parts on a Tormach. Clearly tools have limits, but online discussions seem to overstate those limits more frequently than understating them.

- This applies to programming languages too. There are plenty of online communities (and one particular one I won’t mention) who seem to believe that the choice of programming language or paradigm is the most important thing, not only to the success of a projects and companies, but to the very existence of our field. Little evidence seems to back these strong assertions.