About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

Lambda Snapstart, and snapshots as a tool for system builders

Yesterday, AWS announced Lambda Snapstart, which uses VM snapshots to reduce cold start times for Lambda functions that need to do a lot of work on start (starting up a language runtime3, loading classes, running static code, initializing caches, etc). Here’s a short 1 minute video about it:

Or, for a lot more context on Lambda and how we got here5:

Snapstart is a super useful capability for Lambda customers. I’m extremely proud of the work the team did to make it a reality. We’ve been talking about this work for over two years, and working on it for longer. The team did some truly excellent engineering work to make Snapstart a reality.

Beyond Snapstart in Lambda, I’m also excited about the underlying technology (microVM snapshots), and the way they give us (as system builders and researchers) a powerful tool for building new kinds of secure and scalable systems. In this post, I talk about some interesting aspects of Snapstart, and how they point to interesting possible areas for research on systems, storage, and even cryptography.

What is Snapstart?

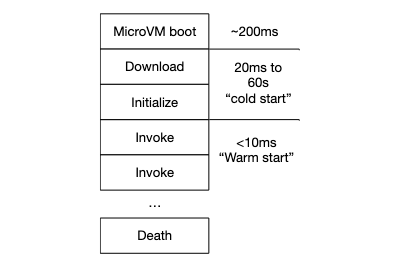

Without snapstart, the cold start time of a Lambda function is a combination of time time taken to download the function (or container), to start the language runtime3, and to run any initialization code inside the function (including any static code, doing class loading, and even JIT compilation). The cold start time doesn’t include MicroVM boot, because that time is not specialized to the application, and can be done in advance. A cold start looks like this1:

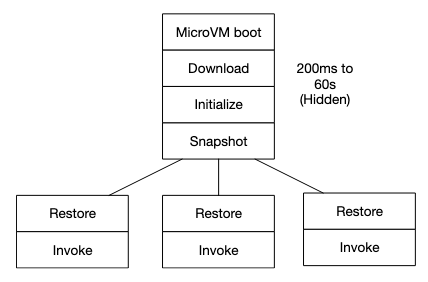

With snapstart, a snapshot of the microVM is taken after these initialization steps (including all the memory, device state, and CPU registers). This snapshot can be used multiple times (also called cloned), to create multiple sandboxes that are initialized in the same way. Cloning like this has two benefits:

- The work of initialization is amortized over many sandboxes, rather than being done once for every sandbox. Lambda runs one sandbox for ever concurrent function execution, so for a function with N concurrent executions this reduces initialization work from O(N) to O(1).

- The time taken by execution no longer accrues to the cold-start time, significantly reducing cold start latency for applications that do a lot of work on startup (which is typically applications that use large language runtimes like the JVM, or large frameworks and libraries).

- JIT compilation and other warmup tasks can be done at initialization time, often avoiding the uneven performance that can be introduced by JITing soon after language runtime2 startup.

In diagram form, the snapstart startup regime looks like this1:

The Problems of Uniqueness

Perhaps the biggest challenge with clones is that they’re, well, clones. They contain the same CPU, the same memory, and even the same CPU registers. Being too alike can cause problems. For example, as we say in Restoring Uniqueness in MicroVM Snapshots:

Most modern distributed systems depend on the ability of nodes to generate unique or random values. RFC4122 version 4 UUIDs are widely used as unique database keys, and as request IDs used for log correlation and distributed tracing. …

and

Many common distributed systems protocols, including consensus protocols like Paxos, and ordering protocols like vector clocks, rely on the fact that participants can uniquely identify themselves.

and

Cryptography is the most critical application of unique data. Any predictability in the data used to generate cryptographic keys—whether long-lived keys for applications like storage encryption or ephemeral keys for protocols like TLS fundamentally compromise the confidentiality and authentication properties offered by cryptography.

In other words, its really important for systems to be able to generate random numbers, and MicroVM clones might find that difficult to do. If they rely on hardware features like rdrand then there’s no problem, but any software-based PRNGs will simply create the same stream of numbers unless action is taken. To solve this problem, our team has been working with the OpenSSL, Linux, and Java open source communities to make sure that common PRNGs like java.security.SecureRandom and /dev/urandom reseed correctly when snapshots are cloned.

State

Another challenge with working with clones is connection state in protocols like TCP. There are actually two problems here:

- Time. If a connection is established during initialization and the clone is used later, it’s likely that the remote end has given up on the connection.

- State. Protocols like TCP provide reliable delivery using state at each end of a connection (like a sequence number), with the assumption that there is one client for the lifetime of the connection. If that one client suddenly becomes two clients, the protocol is broken and the connection must be dropped.

The simple solution is to reestablish connections after snapshots are restored. As with reseeding PRNGs, this requires time and work, especially for secure protocols like TLS, which somewhat dilutes cold start benefit. There’s a significant research and development opportunity here, focusing on fast reestablishment of secure protocols, clone-aware protocols, clone-aware proxies, and even deeply protocol-aware session managers (like RDS proxy)7.

Moving Data

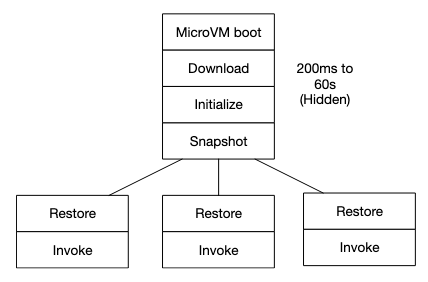

Let’s take another look at this snapstart diagram:

If the clones are running on the same machine the snapshot was created on, then this diagram is reasonably accurate. However, if we want to scale snapshot restores out over a system the size of AWS Lambda, then we need to make sure the snapshot data is available where and when it is needed. This hidden work - both in distributing data when it’s needed and in sending restores to the right places to meet the data - was the largest challenge of building Snapstart. Turning memory reads into network storage accesses, as would happen with a naive demand-loading system, would very quickly cancel out the latency benefits of Snapstart.

We’re going to say more about our particular solution to this problem in the near future, but I believe that there are interesting general challenges here for systems and storage researchers. Loading memory on demand can be done if the data layer offers low-enough latency, close enough to the latency of a local memory read. We can also avoid loading memory on demand by predicting memory access patterns, loading memory contents ahead of when they are needed. This seems hard to do in general, but is significantly simplified by the ability to learn from the behavior of multiple MicroVM clones.

Layers Upon Layers

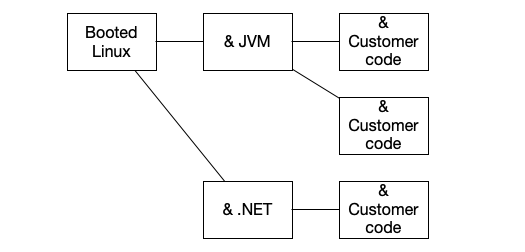

There are multiple places where we can snapshot a MicroVM: just after its booted, after a language runtime has been started, or after customer code initialization. In fact, we don’t have to choose just one of these. Instead, we can snapshot after boot, restore that snapshot to start the language runtime, and store just the changes. Then restore that snapshot, run customer initialization, and store just those changes. This has the big benefit of creating a tree of snapshots, where the same Linux kernel or runtime chunks don’t need to be downloaded again and again.

Unlike traditional approaches to memory deduplication (like Kernel Samepage Merging) there’s no memory vs. CPU tradeoff here: identical pages are shared based on their provenance rather than on post-hoc scanning6. This significantly reduces the scope of the data movement challenge, by requiring widely-used components to be downloaded infrequently, reducing data movement by as much as 90% for common workloads.

Incremental snapshotting also allows us to use seperate cryptographic keys for different levels of data, including service keys for common components, and per-customer and customer-controlled keys for customer data.

Hungry, Hungry Hippos

Linux, rather famously, loves to eat all the memory it can lay its hands on. In the traditional single-system setting this is the right thing to do: the marginal cost of making an empty memory page full is very nearly zero, so there’s no need to think much about the marginal benefit of keeping around a disk-backed page of memory (whether its an mmap mapping, or an IO buffer, or whatever). However, in cloud settings like Lambda Snapstart, this calculus is significantly different: keeping around disk-backed pages that are unlikely to be used again makes snapshots bigger, with little benefit. The same applies to caches at all layers, whether they’re in the language runtime, in application code, or in libraries.

Tools like DAMON provide a good ability to monitor and control the kernel’s behavior. I think, though, that there will be a major change in thinking required as systems like Snapstart become more popular. There seems to be an open area of research here, in adapting caching behaviors (perhaps dynamically) to handle changing marginal costs of full and empty memory pages. Linux’s behavior - and the one most programmers build into their applications - is one behavior on a larger spectrum, that is only optimal at the point of zero marginal cost.

Snapshots Beyond Snapstart

I can’t say anything here about future plans for using MicroVM snapshots at AWS. But I do believe that they are a powerful tool for system designers and researchers, which I think are currently under-used. Firecracker has the ability to restore a MicroVM snapshot in as little as 4ms (or about 10ms for a full decent-sized Linux system), and it’s no doubt possible to optimize this further. I expect that sub-millisecond restore times are possible, as are restore times with a CPU cost not much higher than a traditional fork (or even a traditional thread start). This reality changes the way we think about what VMs can be used for - making them useful for much smaller, shorter-lived, and transient applications than most would assume.

Firecracker’s full and incremental snapshot support is already open source, and already offers great performance and density4. But Firecracker is far from the last word in restore-optimized VMMs. I would love to see more research in this area, exploring what is possible from user space and kernel space, and even how hardware virtualization support can be optimized for fast restores.

In Video Form

Most of this post covers material I also covered in this talk, if you’d prefer to consume it in video form.

Footnotes

- Diagram from Brooker et al, Restoring Uniqueness in MicroVM Snapshots, 2021.

- I particularly enjoyed Laurence Tratt’s recent look at VM startup in More Evidence for Problems in VM Warmup.

- In this post I’ve used the words language runtime to refer to language VMs like the JVM, to avoid confusion with virtualization VMs like Firecracker MicroVMs. This isn’t quite the right word, but it seemed worth avoiding the potential for confusion.

- As we covered in detail in Firecracker: Lightweight Virtualization for Serverless Applications at NSDI’20.

- I really like the compute cache framing that Peter uses in this keynote (from 1:00:30 onwards). It’s different from the one that I use in this post, but very clearly explains why cold starts exist, and why they matter to customers of systems like Lambda. The discussion of being unwilling to compromise on security is also important, and has been a driving force behind our work in this space for the last seven years.

- Granted, this does miss some merge opportunities for pages that end up becoming identical over time, but in a world of crypto and ASLR that happens infrequently anyway.

- One interesting approach is the one described by Erika Hunhoff and Eric Rozner in Network Connection Optimization for Serverless Workloads. Unfortunately, they don’t seem to have taken this work further.