About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

MemoryDB: Speed, Durability, and Composition.

Earlier this week, my colleagues Yacine Taleb, Kevin McGehee, Nan Yan, Shawn Wang, Stefan Mueller, and Allen Samuels published Amazon MemoryDB: A fast and durable memory-first cloud database1. I’m excited about this paper, both because its a very cool system, and because it gives us an opportunity to talk about the power of composition in distributed systems, and about the power of distributed systems in general.

But first, what is MemoryDB?

Amazon MemoryDB for Redis is a durable database with microsecond reads, low single-digit millisecond writes, scalability, and enterprise security. MemoryDB delivers 99.99% availability and near instantaneous recovery without any data loss.

or, from the paper:

We describe how, using this architecture, we are able to remain fully compatible with Redis, while providing single-digit millisecond write and microsecond-scale read latencies, strong consistency, and high availability.

This is remarkable: MemoryDB keeps compatibility with an existing in-memory data store, adds multi-AZ (multi-datacenter) durability, adds high availability, and adds strong consistency on failover, while still improving read performance and with fairly little cost to write performance.

How does that work? As usual, there’s a lot of important details, but the basic idea is composing the in-memory store (Redis) with our existing fast, multi-AZ transaction journal2 service (a system we use in many places inside AWS).

Composition

What’s particularly interesting about this architecture is that the journal service doesn’t only provide durability. Instead, it provides multiple different benefits:

- durability (by synchronously replicating writes onto storage in multiple AZs),

- fan-out (by being the replication stream replicas can consume),

- leader election (by having strongly-consistent fencing APIs that make it easy to ensure there’s a single leader per shard),

- safety during reconfiguration and resharding (using those same fencing APIs), and

- the ability to move bulk data tasks like snapshotting off the latency-sensitive leader boxes.

Moving these concerns into the Journal greatly simplifies the job of the leader, and minimized the amount that the team needed to modify Redis. In turn, this makes keeping up with new Redis (or Valkey) developments much easier. From an organizational perspective, it also allows the team that owns Journal to really focus on performance, safety, and cost of the journal without having to worry about the complexities of offering a rich API to customers. Each investment in performance means better performance for a number of AWS services, and similarly for cost, and investments in formal methods, and so on. As an engineer, and engineering leader, I’m always on the look out for these leverage opportunities.

Of course, the idea of breaking systems down into pieces separated by interfaces isn’t new. It’s one of the most venerable ideas in computing. Still, this is a great reminder of how composition can reduce overall system complexity. The journal service is a relatively (conceptually) simple system, presenting a simple API. But, by carefully designing that API with affordances like fencing (more on that later), it can remove the need to have complex things like consensus implementations inside its clients (see Section 2.2 of the paper for a great discussion of some of this complexity).

As Andy Jassy says:

Primitives, done well, rapidly accelerate builders’ ability to innovate.

Distribution

It’s well known that distributed systems can improve durability (by making multiple copies of data on multiple machines), availability (by allowing another machine to take over if one fails), integrity (by allowing machines with potentially corrupted data to drop out), and scalability (by allowing multiple machines to do work). However, it’s often incorrectly assumed that this value comes at the cost of complexity and performance. This paper is a great reminder that assumption is not true.

Let’s zoom in on one aspect of performance: consistent latency while taking snapshots. MemoryDB moves snapshotting off the database nodes themselves, and into a separate service dedicated to maintaining snapshots.

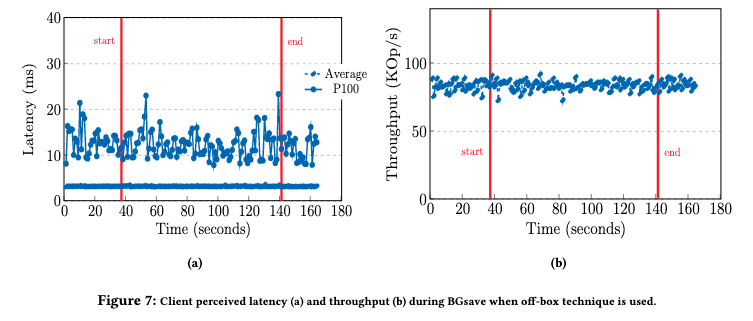

This snapshotting service doesn’t really care about latency (at least not the sub-millisecond read latencies that the database nodes worry about). It’s a throughput-optimized operation, where we want to stream tons of data in the most throughput-efficient way possible. By moving it into a different service, we get to avoid having throughput-optimized and latency-optimized processes running at the same time (with all the cache and scheduling issues that come with that). The system also gets to avoid some implementation complexities of snapshotting in-place. From the paper, talking about the on-box BGSave snapshotting mechanism:

However, there is a spike on P100 latency reaching up to 67 milliseconds for request response times. This is due to the fork system call which clones the entire memory page table. Based on our internal measurement, this process takes about 12ms per GB of memory.

and things get worse if there’s not enough memory for the copy-on-write (CoW) copy of the data:

Once the instance exhausts all the DRAM capacity and starts to use swap to page out memory pages, the latency increases and the throughput drops significantly. […] The tail latency increases over a second and throughput drops close to 0…

the conclusion being that to avoid this effect database nodes need to keep extra RAM around (up to double) just to support snapshotting. An expensive proposition in an in-memory database! Moving snapshotting off-box avoids this cost: memory can be shared between snapshotting tasks, which significantly improves utilization of that memory.

The upshot is that, in MemoryDB with off-box snapshotting, performance impact is entirely avoided. Distributed systems can optimize components for the kind of work they do, and can use multi-tenancy to reduce costs.

Conclusion

Go check out the MemoryDB team’s paper. There’s a lot of great content in there, including a smart way to ensure consistency between the leader and the log, a description of the formal methods the team used, and operational concerns around version upgrades. This is what real system building looks like.

Bonus: Fencing

Above, I mentioned how fencing in the journal service API is something that makes the service much more powerful, and a better building block for real-world distributed systems. To understand what I mean, let’s consider a journal service (a simple ordered stream service) with the following API:

write(payload) -> seq

read() -> (payload, seq) or none

You call write, and when the payload has been durably replicated it returns a totally-ordered sequence number for your write. That’s powerful enough, but in most systems would require an additional leader election to ensure that the writes being sent make some logical sense.

We can extend the API to avoid this case:

write(payload, last_seq) -> seq

read() -> (payload, seq) or none

In this version, writers can ensure they are up-to-date with all reads before doing a write, and make sure they’re not racing with another writer. That’s sufficient to ensure consistency, but isn’t particularly efficient (multiple leaders could always be racing), and doesn’t allow a leader to offer consistent operations that don’t call write (like the in-memory reads the MemoryDB offers). It also makes pipelining difficult (unless the leader can make an assumption about the density of the sequences). An alternative design is to offer a lease service:

try_take_lease() -> (uuid, deadline)

renew_lease(uuid) -> deadline

write(payload) -> seq

read() -> (payload, seq) or none

A leader who believes they hold the lease (i.e. their current time is comfortably before the deadline) can assume they’re the only leader, and can go back to using the original write API. If they end up taking the lease, they poll read until the stream is empty, and then can take over as the single leader. This approach offers strong consistency, but only if leaders absolutely obey their contract that they don’t call write unless they hold the lease.

That’s easily said, but harder to do. For example, consider the following code:

if current_time < deadline:

<gc or scheduler pause>

write(payload)

Those kinds of pauses are really hard to avoid. They come from GC, from page faults, from swapping, from memory pressure, from scheduling, from background tasks, and many many other things. And that’s not even to mention the possible causes of error on local_time. We can avoid this issue with a small adaptation to our API:

try_take_lease() -> (uuid, deadline)

renew_lease(uuid) -> deadline

write(payload, lease_holder_uuid) -> seq

read() -> (payload, seq) or none

If write can enforce that the writer is the current lease holder, we can avoid all of these races while still allowing writers to pipeline things as deeply as they like. This still-simple API provides an extremely powerful building block for building systems like MemoryDB.

Finally, we may not need to compose our lease service with the journal service, because we may want to use other leader election mechanisms. We can avoid that by offering a relatively simple compare-and-set in the journal API:

set_leader_uuid(new_uuid, old_uuid) -> old_uuid

write(payload, leader_uuid) -> seq

read() -> (payload, seq) or none

Now we have a super powerful composable primitive that can offer both safety to writers, and liveness if the leader election system is reasonably well behaved.

Footnotes