About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

Why Aren’t We SIEVE-ing?

Long-time readers of this blog will know that I have mixed feelings about caches. One on hand, caching is critical to the performance of systems at every layer, from CPUs to storage to whole distributed architectures. On the other hand, caching being this critical means that designers need to carefully consider what happens when the cache is emptied, and they don’t always do that well1.

Because of how important caches are, I follow the literature in the area fairly closely. Even to a casual observer, it’s obvious that there’s one group of researchers who’ve been on a bit of a tear recently, including Juncheng Yang, Yazhuo Zhang, K. V. Rashmi, and Yao Yue in various combinations. Their recent papers include a real-world analysis of cache systems at Twitter, an analysis of the dynamics of cache eviction, and a novel FIFO-based cache design with some interesting properties.

The most interesting one to me, which I expect anybody who enjoys a good algorithm will get a kick out of, is the eviction algorithm SIEVE (their paper is coming up at NSDI’24). SIEVE is an eviction algorithm, a way of deciding which cached item to toss out when a new one needs to be put in. There are hundreds of these in the literature. At least. Classics including throwing out the least recently inserted thing (FIFO), least recently accessed thing (LRU), thing that’s been accessed least often (LFU), and even just a random thing. Eviction is interesting because it’s a tradeoff between accuracy, speed (how much work is needed on each eviction and each access), and metadata size. The slower the algorithm, the less latency and efficiency benefit from caching. The larger the metadata, the less space there is to store actual data.

SIEVE performs well. In their words:

Moreover, SIEVE has a lower miss ratio than 9 state-of-the-art algorithms on more than 45% of the 1559 traces, while the next best algorithm only has a lower miss ratio on 15%.

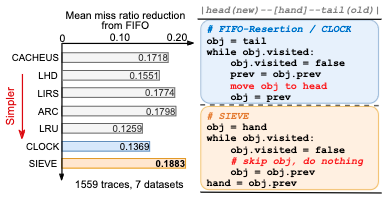

What’s super interesting about SIEVE is that it’s both very effective, and an extremely simple change on top of a basic FIFO queue. Here’s Figure 1 from their paper with the pseudocode:

The only other change is to set obj.visited on access. Like the classic CLOCK (from the 1960s!), and unlike the classic implementation of LRU, SIEVE doesn’t require changing the queue order on access, which reduces the synchronization needed in a multi-tenant setting. All it needs on access is to set a bool, which is a simple atomic operation on most processors. That’s something of a big deal, for an algorithm that performs so well.

Why aren’t we all SIEVE-ing?

SIEVE raises an interesting question - if it’s so effective, and so simple, and so closely related to an algorithm that’s been around forever, why has nobody discovered it already? It’s possible they have, but I haven’t seen it before, and the authors say they haven’t either. Their hypothesis is an interesting one:

In block cache workloads, which frequently feature scans, popular objects often intermingle with objects from scans. Consequently, both types of objects are rapidly evicted after insertion.

and

We conjecture that not being scan-resistant is probably the reason why SIEVE remained undiscovered over the decades of caching research, which has been mostly focused on page and block accesses.

That’s believable. Scan resistance is important, and has been the focus of a lot of caching improvements over the decades2. Still, it’s hard to believe that folks kept finding this, and kept going nah, not scan resistant and tossing it out. Fascinating how these things are discovered.

Scan-resistance is important for block and file workloads because these workloads tend to be a mix of random access (update that database page, move that file) and large sequential access (backup the whole database, do that unindexed query). We don’t want the hot set of the cache that makes the random accesses fast evicted to make room for the sequential4 pages that likely will never be accessed again3.

A Scan-Resistant SIEVE?

This little historical mystery raises the question of whether there are similarly simple, but more scan-resistant, approaches to cache eviction. One such algorithm, which I’ll call SIEVE-k, involves making a small change to SIEVE.

- Each item is given a small counter rather than a single access bit,

- On access the small counter is incremented rather than set, saturating at the value

k, - When the eviction

handgoes past, the counter is decremented (saturating at 0), rather than reset.

My claim here is that the eviction counter will go up for the most popular objects, causing them to be skipped in the round of evictions kicked off by the scan. This approach has some downsides. One is that eviction goes from worst-case O(N) to worst-case O(kN), and the average case eviction also seems to go up by k (although I don’t love my analysis there). The other is that this could delay eviction of things that need to be evicted. Balancing these things, the most interesting variant of SIEVE-k is probably SIEVE-2 (along with SIEVE-1, which is the same as Zhang et al’s original algorithm).

Does It Work?

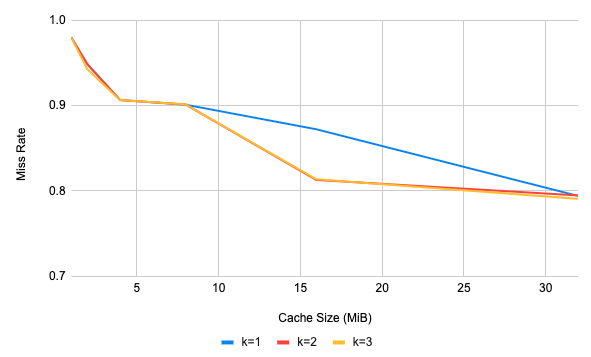

Yeah. Sort of. First, let’s consider a really trivial case of a Zipf-distributed base workload, and a periodic linear scan workload that turns on and off. In this simple setting SIEVE-2 out-performs SIEVE-1 across the board (lower miss rates are better).

Clearly, with the 16MiB cache size here, SIEVE-2 and SIEVE-3 are doing a better job than SIEVE of keeping the scan from emptying out the cache. Beyond this magic size, it performs pretty much identically to SIEVE-1.

But the real-world is more complicated than that. Using the excellent open source libCacheSim I tried SIEVE-2 against SIEVE on a range of real-world traces. It was worse than SIEVE across the board on web-cache style KV workloads, as expected. Performance on block workloads5 was a real mixed bag, with some wins and some losses. So it seems like SIEVE-k is potentially interesting, but isn’t a win over SIEVE more generally.

If you’d like to experiment some more, I’ve implemented SIEVE-k in a fork of libCacheSim.

Updates

The inimitable Keegan Carruthers-Smith writes:

I believe there is an improvement on your worst case for SIEVE-k eviction from O(kN) to O(N): When going through the list, keep track of the minimum counter seen. Then if you do not evict on the first pass, decrement by that minimum value.

Which is, indeed, correct and equivalent to what my goofy k-pass approach was doing (only k/2 times more efficient). He also pointed out that other optimizations are possible, but probably not that interesting for small k.

And, on the fediverse, Tobin Baker pointed out something important about SIEVE compared to FIFO and CLOCK: removing items from the middle of the list (rather than the head or tail only) means that the simple circular array approach doesn’t work. The upshot is needing O(log N) additional state6 to keep a linked list. Potentially an interesting line of investigation for implementations that are very memory overhead sensitive or CPU cache locality sensitive (and scanning through entries in a random order rather than sequentially). Tobin then pointed out an interesting potential fix:

A simple fix to the SIEVE algorithm to accommodate circular arrays would be to move the current tail entry into the evicted entry’s slot (much like CLOCK copies a new entry into the evicted entry’s slot). This is really not very different from the FIFO-reinsertion algorithm, except that its promotion method (moving promoted entries to evicted slots) preserves the SIEVE invariant of keeping new entries to the right of the “hand” and old entries to the left.

This one is interesting, and I don’t have a good intuition for how it would affect performance (or whether the analogy to FIFO-reinsertion is correct). Implementing it in libCacheSim would likely sort that out.

Footnotes

- Partially because it’s hard to do. We need better tools for reasoning about system behavior.

- Including Betty O’Neil’s The LRU-K Page Replacement Algorithm For Database Disk Buffer, a classic approach to scan resistance from the 90s database literature.

- It’s worth mentioning that some caches solve this by hoping that clients will let them know when data is only going to be accessed once (like with

POSIX_FADV_NOREUSEandPOSIX_FADV_DONTNEED). This can be super effective with the right discipline, but storage systems in general can’t make these kinds of assumptions (and often don’t have these kinds of interfaces at all). - I say sequential here, but it’s really not sequential access that matters. What matters is that scans tend to happen at a high rate, and that they introduce a lot of one hit wonders (pages that are read once and never again, and therefore are not worth caching). Neither of those criteria need sequential access, but it happens to be true that they come along most often during sequential accesses.

- Block traces are interesting, because they tend to represent a kind of residue of accesses after the easy caching has already been done (by the database engine or OS page cache), and so represent a pretty tough case for cache algorithms in general.

- Which can be halved by committing unspeakable evil.