About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

What is Backoff For?

Years ago I wrote a blog post about exponential backoff and jitter, which has turned out to be enduringly popular. I like to believe that it’s influenced at least a couple of systems to add jitter, and become more stable. However, I do feel a little guilty about pushing the popularity of jitter without clearly explaining what backoff and jitter do, and do not do.

Here’s the pithy statement about backoff:

Backoff helps in the short term. It is only valuable in the long term if it reduces total work.

Consider a system that suffers from short spikes4 of overload. That could be a flash sale, top-of-hour operational work, recovery after a brief network partition, etc. During the overload, some calls are failing, primarily due to the overload itself. Backing off in this case is extremely helpful: it spreads out the spike, and reduces the amount of chatter between clients and servers. Jitter is especially effective at helping broaden spikes. If you want to see this in action, look at the time series in the exponential backoff and jitter post.

Now, consider a long spike of overload. There are two cases here.

One is where we have a large (maybe effectively unlimited) number of clients, and they’re independently sending work. For example, think about a website with a million customers, each visiting it about once a day. Each client backing off in this case does not help, because it does not reduce the work being sent to the system. Each client is still going to press F5 the same number of times, so delaying their presses doesn’t help.

The other is where we have a smaller number of clients, each sending a serial stream of requests. For example, think of a fleet of workers polling a queue. Each client backing off in this case helps a lot because they are serial. Backing off means they send less work, and less is asked of the service1.

That may sound like a subtle distinction, but the bottom line is this: does backoff actually reduce the work done? In the case of lots of clients, it doesn’t, because each new client entering the system doesn’t know other have backed off.

The only way to deal with long-term overload is to reduce load, deferring load does not work.

Now, on to retries. As I wrote about in Fixing retries with token buckets and circuit breakers, retries have an amplifying effect on the work a service is asked to do. During long-term overload, retries may increase the work to be done. The way to fix that is with a good retry policy, such as the token bucket based adaptive strategy described in the post.

Backoff is not a substitute for a good retry policy.

Backoff is not a good retry policy. Or, at least, is hard to use as one.

Backoff is only a good retry policy in systems with small numbers of sequential clients, where the introduced delay between retries delays future first tries. If this property is not true, and the next first try is going to come along at a time independent of retry backoff, then backing off retries does nothing to help long-term overload. It just defers work to a future time2.

That doesn’t mean that backing off between retries is a bad idea. It’s a good idea, but only helps for short term overload (spikes, etc). It does not reduce the total work in the system, or total amplification factor of retries.

A good approach to retries combines backoff, jitter, and a good retry policy.

These are complimentary mechanisms, and neither solves the whole problem.

First tries and second tries

The other way to think about this is to think about first tries and second tries. A first try is the first time a given client tries to do a piece of work. There are two ways systems can get overloaded: too many first tries and too many second tries.

If you have too many first tries, you need to have fewer. If you’ve got a bounded number of clients, getting each of them to back off is an effective strategy3. With a bounded number of clients, backoff is an effective way to do that. If you have an unbounded number of clients, backoff is not an effective way to do that. They only hear the bad news after their first try, so no amount of backoff will reduce their first try rate.

If you’ve got an OK number of first tries, but some error rate is driving up second try (retry traffic), then you need to reduce the number of second tries. Backoff is an effective way to reduce the number of second tries now, by deferring them into the future. If you think you’ll be able to handle them better in the future, that’s a win. But backoff is not an effective way to reduce the overall number of second tries in total for long-running overload. For that, you need something like the adaptive retry approach.

Unless, of course, your clients are relatively small in number, and their next first try is only going to get made after this round of second tries is done. Then backoff will reduce the overall rate of second tries.

This ‘number of clients’ thinking can be a bit confusing, because it’s not really about number of clients. Its about the number of parallel things doing work. Code that spawns a thread for each call, or dispatch each call to an event loop, can become an effectively unbounded number of things.

Simulation Results

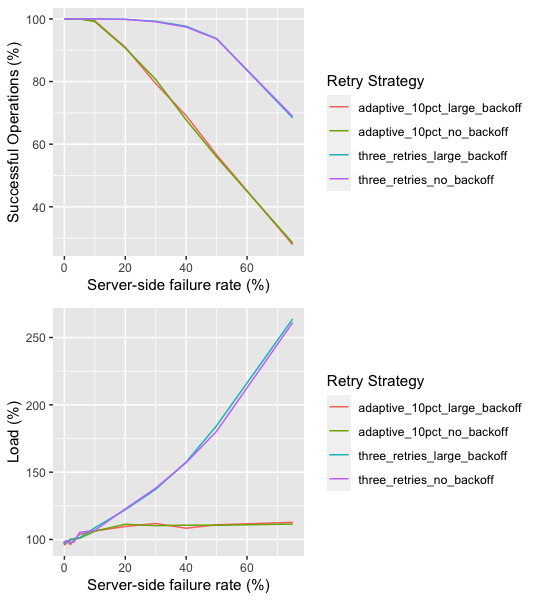

We can validate these assertions by looking at some simulation results. First, let’s look at a simulation that compares four strategies: three retries with and without backoff, and adaptive with and without backoff, for a case with a very large number of clients. What we see in these results matches the assertions: in this case, which reflects a long-running overload with an unbounded number of clients, per-request retry backoff has nearly no effect on traffic amplification.

Again, the unbounded number of clients can mean lots of clients, or just clients that spawn threads or async work for requests. The important property is whether they wait on a request to be done (or fail) before they do the next one.

But the news is not all bad. As soon as we have a limited number of serial clients, we see that backoff is effective at avoiding amplification of retries, and at reducing the number of first tries. In this case, backoff is very effective at improving the behavior of the system. The results for adaptive retry are similar, and show that backoff is similarly useful.

Footnotes

- You may be wondering here about famous and super successful systems like TCP and Ethernet CSMA/CD which use backoff approaches like exponential backoff and AIMD very effectively. The same reasoning applies to them: their backoff strategies are only effective because the number of clients is relatively small, and slowing clients down reduces overall work in the system (helping it find a new dynamic set point).

- It may even delay recovery after overload because those deferred backoffs are a kind of implicit queue of work that needs to be done before the system is fully recovered.

- Again, this is what TCP does.

- I keep saying short and long without a lot of details. Roughly, short means a time approximately around the time clients are willing to wait, and long is longer than that.