About Me

My name is Marc Brooker. I've been writing code, reading code, and living vicariously through computers for as long as I can remember. I like to build things that work. I also dabble in machining, welding, cooking and skiing.I'm currently an engineer at Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Seattle, where I work on databases, serverless, and serverless databases. Before that, I worked on EC2 and EBS.

All opinions are my own.

Links

My Publications and Videos@marcbrooker on Mastodon @MarcJBrooker on Twitter

Erasure Coding versus Tail Latency

Jeff Dean and Luiz Barroso’s paper The Tail At Scale popularized an idea they called hedging, simply sending the same request to multiple places and using the first one to return. That can be done immediately, or after some delay:

One such approach is to defer sending a secondary request until the first request has been outstanding for more than the 95th-percentile expected latency for this class of requests.

Smart stuff, and has become something of a standard technique for systems where tail latencies are a high multiple of the 50th or 95th percentile latencies1. The downside of hedged requests is that it’s all-or-nothing: you either have to send twice, or once. They’re also modal, and don’t do much to help against lower percentile latencies. There’s a more general technique available that has many of the benefits of hedged requests, with improved flexibility and power to reduce even lower percentile latencies: erasure coding.

What is Erasure Coding?

Erasure coding is the idea that we can take a blob of data, break it up into M parts, in such a way that we can reconstruct it from any k of those M parts2. They’re pretty ubiquitous in storage systems, block storage, object storage, higher RAID levels, and so on. When storage systems think about erasure codes, they’re usually thinking about durability: the ability of the system to tolerate $M - k$ disk or host failures without losing data, while still having only $\frac{M - k}{M}$ storage overhead. The general idea is also widely used in modern communication and radio protocols3. If you’re touching your phone or the cloud, there are erasure codes at work.

I won’t go into the mathematics of erasure coding here, but will say that it is somewhat remarkable to me that they exist for any combination of k and M (obviously for $k \leq M$). It’s one of those things that’s both profound and obvious, at least to me.

Erasure Coding for Latency

Say I have an in-memory cache of objects. I can keep any object in the cache once, and always go looking for it in that one place (e.g. with consistent hashing). If that place is slow, overloaded, experiencing packet loss, or whatever, I’ll see high latency for all attempts to get that object. With hedging I can avoid that, if I store the object in two places rather than one, at the cost of doubling the size of my cache.

But what if I wanted to avoid the slowness and not double the size of my cache? Instead of storing everything twice, I could break it into (for example) 5 pieces ($M = 5$) encoded in such a way that I could reassemble it from any four pieces ($k = 4$). Then, when I fetch, I send five get requests, and have the whole object as soon as four have returned. The overhead here on requests is 5x, on bandwidth is worst-case 20%, and on storage is 20%. The effect on tail latency can be considerable.

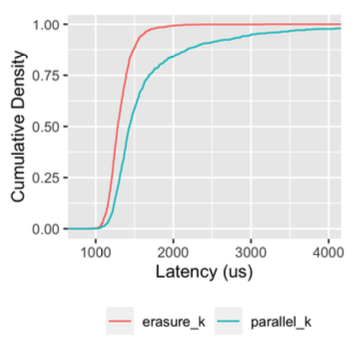

The graph below, from an upcoming paper where we describe the storage system we built for Lambda container support and SnapStart, shows the measured latency of a 4-of-5 erasure coding scheme, versus the latency we would have experience from simply fetching 4-of-4 shards in parallel.

The huge effect on the tail here is obvious. What’s also worth paying attention to is that, unlike hedging-style schemes, there’s also a considerable win here at the lower percentiles like the median. In fact, the erasure coding scheme drops the median latency by about 20%. Similar wins are reported by Rashmi et al in EC-Cache: Load-Balanced, Low-Latency Cluster Caching with Online Erasure Coding, and many others.

Erasure Coding for Availability

Erasure coding in this context doesn’t only help with latency. It can also significantly improve availability. Let’s think about that cache again: when that one node is down, overloaded, busy being deployed, etc that object is not available. This property can make operating high hit-rate caches and storage systems particularly difficult: any kind of deployment or change can look to clients like a kind of rolling outage. However, with erasure coding, single failures (or indeed any $M - k$ number of failures) have no availability impact.

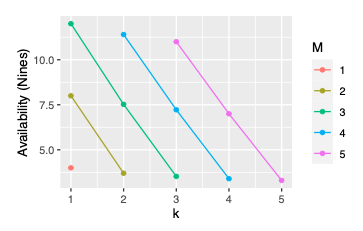

How big this effect is depends on M and k. In the graph below, we look at the availability impact of various combinations of M and k, assuming that each component offers 99.99% (four nines) availability (and assuming independent failures).

These are straight lines on an exponential axis, meaning (at least with these numbers) we get exponential improvement at linear cost as we increase k! How often do you get a deal like that?

Erasure Coding for Load and Spread

The flexibility of erasure coding also gives us a lot of control in how we spread out load, and avoid overheating particular nodes. For example, imagine we were using a scheme with $k = 2$ and $M = 10$. The write cost is rather high (10 writes), the storage cost is rather high (5x), but we have a huge amount of flexibility about where we send traffic. A request could ask any 2 or more of the 10 nodes and still get the entire answer, which means that a load-balancer could be very effective at spreading out load. Simple replication (aka $k = 1$) has the same effect, but isn’t quite as flexible.

Conclusion

Erasure Coding is a ubiquitous technique in storage and physical networking, but something of an under-rated and under-used one in systems more generally. Next time you build a latency-sensitive or availability-sensitive cache or storage system, it’s worth considering. There are many production systems that do this already, but it doesn’t seem to be as widely talked about as it deserves.

Footnotes

- Although their argument for why it doesn’t add additional load tends to break down when we think about failure cases, and especially when we apply the lens of metastable failures. In the paper, they say:

Although naive implementations of this technique typically add unacceptable additional load, many variations exist that give most of the latency-reduction effects while increasing load only modestly. One such approach is to defer sending a secondary request until the first request has been outstanding for more than the 95th-percentile expected latency for this class of requests.

This will, in the normal case, limit the number of hedged requests to around 5%. But what if there’s a correlated latency increase across the system (caused by traffic, infrastructure failures, or an empty cache, for example) which raises all request latencies to the 95th-percentile expected latency. At least until you update your expectation, you’ve doubled your traffic, and perhaps added more cancellation traffic. For this reason, this technique should always be combined with an approach like a token bucket that limits the additional requests to what you’d expect (say 5%). The same token bucket we use for adaptive retries works well here.

-

When I say “any k” I’m referring to one class of codes, the maximum distance separable codes. There are whole families of non-MDS code that have other interesting properties, but only allow reconstruction from some combinations.

-

The ability of Forward Error Correction (FEC) to lift useful data out of the noise floor is truly remarkable.